Frequent attenders of health-care services are characterised by high rates of physical and psychiatric illness as well as social problems (Reference Karlsson, Joukamaa and LahtiKarlsson et al, 1997). These patients, observed in all medical settings, account for a major proportion of medical resources (Reference McFarland, Freeborn and MulloolyMcFarland et al, 1985; Reference Garfinkel, Riley and lannacchinoeGarfinkel et al, 1988). Many frequent attenders have chronic or recurrent physical symptoms that cannot be explained adequately by somatic disease. Our knowledge of medically unexplained symptoms suggests that repeated referral and investigation often is an unhelpful and costly approach to management. However, most secondary care studies involving medically unexplained symptoms have focused upon new patients (Reference Hamilton, Campos and CreedHamiltonet al, 1996) or psychiatric referrals (Reference Shaw and CreedShaw & Creed, 1991). Because little is known about those patients who are frequent or repeat attenders, we undertook a study across the South Thames (West) National Health Service (NHS) Region in which we identified medically unexplained consultations in frequent attenders of secondary care (Reference Reid, Wessely and CrayfordReid et al, 2001). The present study estimates the overall service use and costs of frequent attenders presenting repeatedly with unexplained symptoms, and compares them with other frequent attenders.

METHOD

The South Thames (West) NHS Region database of out-patient hospital activity was used to identify frequent attenders over a 3-year period from 1993 to 1996 (Reference Reid, Wessely and CrayfordReid et al, 2001). A population was defined in which potential subjects were all patients in the region aged 18-65 years who had a new appointment to secondary medical or surgical care in 1993. The following condition-specific specialities were excluded from the sample because referred patients were unlikely to be presenting with medically unexplained symptoms: obstetrics (but not gynaecology), oncology, clinical genetics, palliative medicine, transplantation surgery and nuclear medicine. Psychiatry also was excluded because in this case medically unexplained symptoms would be the reason for referral.

Patients were followed over a 3-year period to assess their overall service use within the region by counting all out-patient appointments. The population was stratified into two age groups (18-45 years and 46-65 years), to account for the expected increased consultation rates in the older age group. Frequent attenders then were defined as the top 5% of out-patient attenders (by number of appointments) and 200 patients were selected randomly from each age stratum for inclusion in the study. The study was approved by the local research ethics committee.

The medical records of each subject were examined by a medically qualified investigator between September and December 1998. Every new referral (consultation episode) during the 3-year period was recorded, as were details of appointments, clinical investigations, treatment and disposal. Then it was determined whether each episode was medically unexplained, explained, mixed in nature (evidence of both physical and psychological disorder) or factitious. Criteria for a medically unexplained episode consisted of the following: the patient presented with physical symptoms; the patient received investigations for the physical symptoms; and the investigations and clinical examination revealed either no abnormality or abnormalities that were thought to be trivial or incidental.

A symptom was designated ‘definitely medically unexplained’ if there was evidence of a thorough investigation of the symptoms, all of which were negative, and either psychosocial reasons were suggested for the presentation or a diagnosis was made that implied a medically unexplained syndrome (fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, etc.). An intermediate category, ‘probably medically unexplained’, was used when there was an absence of evidence that a defined organic disease caused the symptom but uncertainty was expressed about the diagnosis or investigations were inconclusive. This method was evaluated in a pilot study involving both liaison psychiatrists and physicians and was found to have good interrater reliability (κ=0.76-0.88) (Reference Reid, Crayford and RichardsReidet al, 1999).

Data analysis

Data were analysed using Stata statistical software, version 5.0 (StataCorp, 1997). For the purpose of analysis, those episodes categorised as definitely or probably unexplained were regarded as medically unexplained consultation episodes. The sample of frequent attenders was grouped according to the number of medically unexplained consultation episodes recorded during the study period.

Somatising patients

The criterion for patients with recurrent medically unexplained episodes was determined a priori as those with two or more unexplained episodes. This group comprised the ‘somatising patient’ category, although the presence of psychiatric morbidity was not a requirement.

Other frequent attenders

The rest of the sample consisted of patients with fewer than two medically unexplained episodes. Because somatising patients were required to have at least two consultation episodes, frequent attenders with just one consultation episode (medically unexplained or otherwise) were excluded from further analysis.

Analysis of costs

The cost of out-patient consultations was determined by speciality and based upon national data (including an element to reflect the cost of capital and support services). These secondary care costs are calculated on a standardised basis and do not allow for variation in the number of investigations undertaken. We therefore performed a separate analysis of costs for investigations alone using local rates. Examples of typical costs for investigations are shown in Table 1. Although cost data were positively skewed, mean rather than median costs are presented because they provide information about the total cost incurred by all patients. Confidence intervals for the difference between mean costs were obtained using the non-parametric bootstrap method with 1000 replications, implemented on Stata Software (StataCorp, 1997).

Table 1 Costs for selected medical investigations (1994-1995 prices)1

| Investigation | Cost (£) |

|---|---|

| Full blood count | 1.90 |

| Urea and electrolytes | 2.67 |

| Liver function test | 5.52 |

| Chest X-ray | 9.69 |

| Lung function test | 35.26 |

| Electrocardiogram | 8.85 |

| Exercise electrocardiogram | 67.41 |

| Abdominal ultrasound | 24.27 |

| Endoscopy | 116.31 |

| Computed tomography brain scan | 58.18 |

| Electroencephalogram | 90.88 |

| Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain | 220.00 |

RESULTS

The medical records of 361 (90%) outpatients were obtained for examination: 6 were unavailable due to litigation or complaint, 24 were recorded as missing and 9 were unavailable because the subjects were deceased; 81 patients had just one consultation episode and thus were excluded from further analysis, leaving 280 frequent attenders with at least two consultation episodes. Following a review of medical records, 61 patients (16.9%) had two or more medically unexplained consultation episodes (somatising patients) and 40 (65.6%) of these also had attended for consultation episodes that were medically unexplained.

The characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 2. There were no differences between the somatising patients and other frequent attenders in terms of gender, ethnicity, employment or marital status. However, somatising patients were more likely to come from the younger age stratum (Mantel—Haenszel odds ratio=2.2, 95% CI 1.2-3.8).

Table 2 Characteristics of somatising patients and other frequent attenders

| Somatising patients, n=61 (%) | Others, n=219 (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 20 (32.8) | 79 (36.1) | 0.64 |

| Female | 41 (67.2) | 140 (63.9) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| <46 | 39 (63.9) | 99 (45.2) | 0.01 |

| ≥ 46 | 22 (36.1) | 120 (54.8) | |

| Employment | |||

| Manual | 12 (19.7) | 50 (22.8) | 0.94 |

| Non-manual | 20 (32.8) | 67 (30.6) | |

| Housewife/husband | 15 (24.6) | 49 (22.4) | |

| Retired/unemployed | 14 (22.9) | 53 (24.2) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 12 (19.7) | 48 (21.9) | 0.92 |

| Married | 42 (68.8) | 142 (64.8) | |

| Separated | 4 (6.6) | 14 (6.5) | |

| Widowed | 3 (4.9) | 15 (6.8) | |

| Ethnic group | |||

| White | 51 (83.6) | 181 (82.6) | 0.86 |

| Non-White | 10 (16.4) | 38 (17.4) |

Table 3 shows the use of secondary care services by frequent attenders. Over three years, somatising patients had significantly more consultation episodes (referrals) in secondary care than other frequent attenders. The total number of appointments attended by the two groups was comparable, suggesting that although somatising patients were referred more frequently, they were discharged (or referred elsewhere) sooner.

Table 3 Number of consultation episodes and total number of hospital appointments

| Somatising patients, median (Q1-Q3)1 | Others, median (Q1-Q3)1 | Mann—Whitney Utest | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consultation episodes | 4 (3-5) | 3 (2-3) | P < 0.001 |

| Hospital appointments | 17 (15-22) | 18 (16-22) | P < 0.95 |

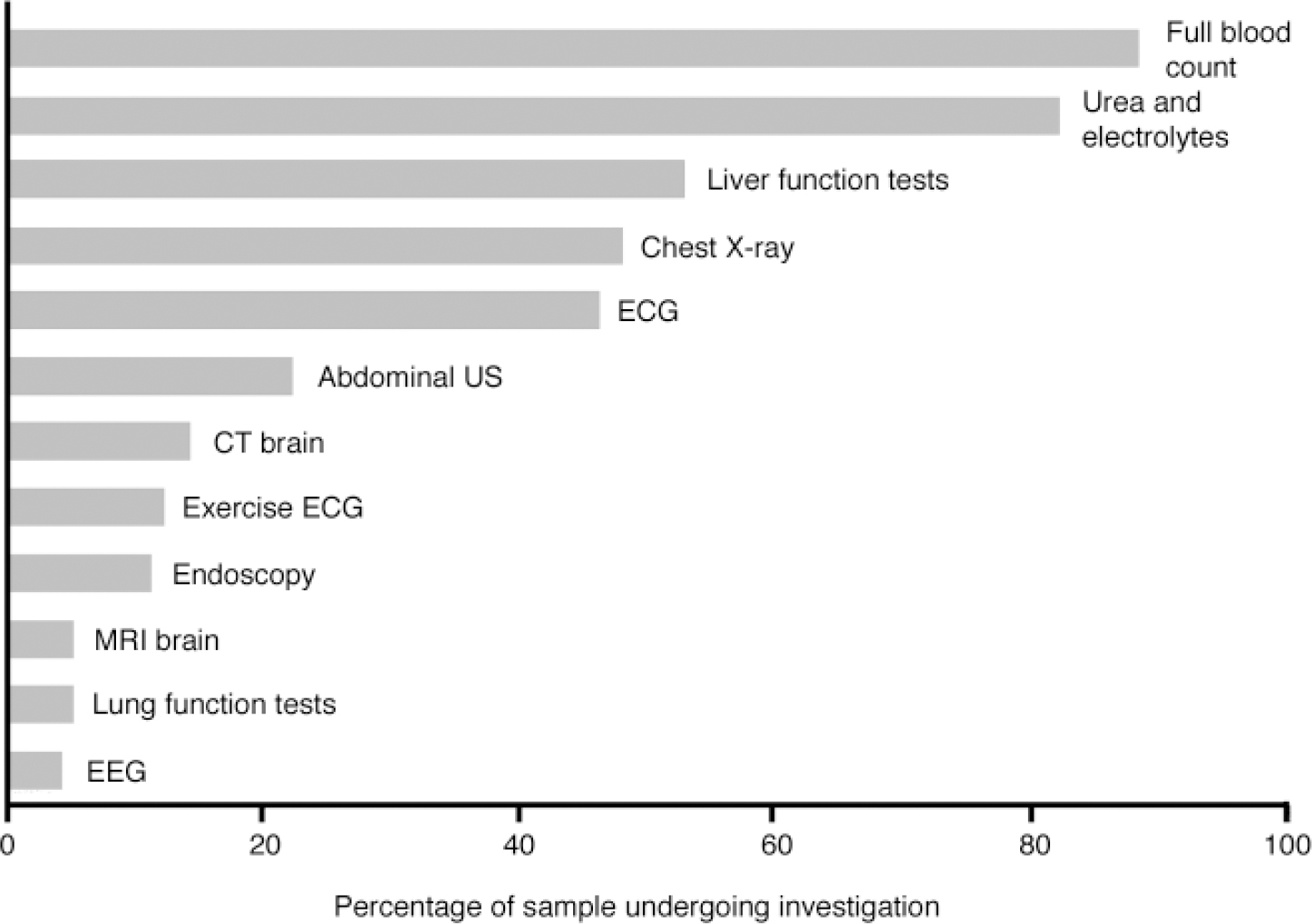

We compared the use of four medical investigations in the sample (Table 4). These were the most frequently requested investigations, with the exception of blood tests, electrocardiograms and X-rays (Fig. 1). All four investigations, most notably the computed tomography brain scan, were used more frequently with the somatising patients.

Fig. 1 Frequency of selected medical investigations in frequent attender sample (CT, computed tomography; ECG, electrocardiogram; EEG, electroencephalogram; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; US, ultrasound).

Table 4 Comparison of the use of four medical investigations

| Investigation | Somatising patients, n=61 (%) | Others, n=219 (%) | Mantel—Haenszel odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computed tomography brain scan | 19 (31) | 19 (8) | 4.8 (2.3-10.0) |

| Exercise electrocardiogram | 12 (20) | 22 (10) | 2.2 (1.0-4.8) |

| Endoscopy (OGD) | 13 (21) | 16 (7) | 3.4 (1.5-7.8) |

| Abdominal ultrasound | 21 (34) | 41 (19) | 2.3 (1.2-4.3) |

Table 5 shows the cost of secondary care for frequent attenders. The mean cost of individual consultation episodes (i.e. from referral to discharge) was significantly lower in somatising patients compared with other frequent attenders. However, when overall costs were calculated for the 3-year period of follow-up, this difference was lost. When medical investigations were considered independently there was a significant difference in expenditure, with investigations for somatising patients being twice as costly.

Table 5 Mean costs for frequent attenders of secondary care

| Mean costs (£) | Mean difference between groups (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Somatising patients | Others | ||

| Costs per consultation episode in secondary care | 226 | 330 | 104 (72-136) |

| Total costs in secondary care | 955 | 882 | 73 (39-185) |

| Cost of investigations | 244 | 124 | 120 (68-172) |

DISCUSSION

Main findings

Almost one in five frequent attenders in this study of secondary care presented repeatedly with medically unexplained symptoms. The number of consultations and the overall expenditure in this group of patients were comparable with other frequent attenders, but when medical investigations were considered independently they were used more frequently and were significantly more costly.

A notable finding is the similar prevalence of frequent attenders with medically unexplained symptoms found in other settings. Karlsson et al (Reference Karlsson, Joukamaa and Lahti1997), in a study of 67 frequent attenders in primary care, identified a group of 14 (20.9%) ‘chronically somatising’ patients who presented with at least three long-lasting symptoms that could not be accounted for by physical illness. In contrast to the substantial literature in primary care, there have been few studies of frequent attenders in the outpatient setting (Reference Gill and SharpeGill & Sharpe, 1999). However, a recent survey of 762 frequent attenders at a gastroenterology clinic found that 159 (21%) had no ‘relevant organic disease’ (Reference Bass, Hyde and BondBass et al, 2001). Fink (Reference Fink1992) investigated frequent admissions (at least 10 admissions in 8 years) to general hospitals in the Danish population. Of 282 frequent attenders, 56 (19%) were identified as ‘persistent somatisers’ with repeated admissions for medically unexplained symptoms. The only population characteristic distinguishing the somatising patients from other frequent attenders was that of age, with the somatising patients being younger. This is unsurprising, given that the prevalence of physical illness generally increases with age. The absence of a female excess in the somatising patients was unexpected, given that this is a near-universal finding in studies of medically unexplained symptoms. This highlights the role that higher consultation rates in females may have as a confounding variable in such studies.

A number of studies in the USA have demonstrated the increased use and cost of health-care resources in patients with medically unexplained symptoms (Reference Escobar, Golding and HoughEscobar et al, 1987; Reference SmithSmith, 1994). In the UK, Shaw & Creed (Reference Shaw and Creed1991) studied 52 somatising patients referred to psychiatry and found that patients had a median of three (range 1-13) out-patient prior appointments with a physician. They also calculated the direct hospital costs involved (median cost per patient of £286; range £25-2300). The authors commented that out-patient attendance accounted for a minority of the overall cost, with the majority being taken up by in-patient admissions and particular medical investigations. In a study of 343 new patients attending cardiology, gastroenterology and neurology out-patient clinics, Hamilton et al (Reference Hamilton, Campos and Creed1996) found no difference in the number of investigations undertaken for functional and organic disorders. However, the cost of investigations was significantly higher for patients with organic disorders: a median of £89 (range £0-323) compared with £ 41 (£0-98). The contrasting use of investigations in comparison with the present study may reflect different approaches to management in new patients and those who go on to become frequent attenders. The initial aim of medical investigations in all patients is to establish or confirm a diagnosis. If a diagnosis is made, then the role of investigations may be limited to monitoring or guiding treatment, whereas in patients with medically unexplained symptoms the search for demonstrable pathology may continue.

Methodological considerations

This study adds to the limited UK literature on the use of health-care resources by patients with medically unexplained symptoms. The inclusion of different hospitals and a range of specialities allowed for a comprehensive record of health-care usage, which is important because these symptoms often involve more than one bodily system and patients may be attending different clinics. A collection rate of 90% for medical records was achieved, which is comparable with that in other studies (Reference Hamilton, Campos and CreedHamilton et al, 1996; Reference Nimnuan, Hotopf and WesselyNimnuan et al, 2001). Frequent attendance in this study was defined using a cutoff of 5% in the distribution of consultation frequency. Because consultation rates in a population are distributed continuously, any threshold for frequent attendance is, by definition, arbitrary. In contrast to previous studies that have used a follow-up period of 12 months, by using a 3-year follow-up the aim was to capture a sample in whom frequent attendance was a persistent rather than transient occurrence (Reference Ward, Underwood and FatovichWard et al, 1994).

One limitation of the study was the retrospective use of medical records for data collection, rather than objective patient assessment. However, details of investigations and final diagnosis generally are well recorded in hospital case notes, as is attendance for out-patient appointments. A further limitation is that the criteria used in defining medically unexplained symptoms, although shown to be reliable (Reference Reid, Crayford and RichardsReid et al, 1999), had undergone no a priori test of validity. Because the setting was secondary medical care, however, the study population had been investigated extensively and followed for a period of 3 years, thus affording a greater degree of confidence in final diagnoses than in primary care or newly referred patients.

The economic evaluation serves as an indicator only of secondary care costs; given the study design, other health-care costs incurred by patients and costs to wider society in terms of social security payments and lost productivity could not be calculated. Furthermore, in-patient admissions — which are potentially a source of major health-care costs — were not included. Despite this, because the patients are, by definition, frequent attenders of secondary care, expenditure in this setting is likely to represent a significant proportion of total health care costs and this evaluation represents a useful step in emphasising the substantial costs incurred with no evident benefit.

Somatisation and medically unexplained symptoms

This study uses the term ‘somatising patient’ to describe those frequent attenders presenting repeatedly with medically unexplained symptoms. As with previous studies (Reference FinkFink, 1992; Reference Portegijs, van der Horst and ProotPortegijs et al, 1996; Reference Karlsson, Joukamaa and LahtiKarlsson et al, 1997), this usage may be criticised because there is a presumption of underlying psychological distress with no supporting evidence. Although emotional problems are common, they are not ubiquitous in medically unexplained symptoms and an overt psychiatric cause often is lacking (Reference Kroenke and MangelsdorffKroenke & Mangelsdorff, 1989). A further complication is the frequent co-occurrence of medically unexplained symptoms and additional physical illness (Reference Katon, von Korff and LinKaton et al, 1990). Two-thirds of the somatising patients in the present study also presented on different occasions with defined medical illness. This overlap makes the detection of somatisation particularly difficult and reduces the likelihood of psychiatric disorder being identified (Reference Bridges and GoldbergBridges & Goldberg, 1985).

That somatisation is a universal phenomenon is well established. As many as 80% of depressed or anxious primary care attenders initially present with exclusively somatic complaints (Reference Bridges and GoldbergBridges & Goldberg, 1985). It seems, however, that a proportion of these patients are not reassured by negative investigations and go on to become frequent attenders in secondary care with repeated referrals and multiple complaints. What remain unclear are the factors that determine such a chronic course. Although patient attributes such as personality characteristics or psychiatric disorder are considered to be important, there is evidence also that the doctor's role in management is significant. Overinvestigation, inappropriate information and advice given to patients and inappropriate prescription of medication were associated with medically unexplained symptoms in a case—control study by Kouyanou et al (Kouyanou et al, Reference Kouyanou, Pither and Wessely1997, Reference Kouyanou, Pither and Rabe-Hesketh1998), suggesting that these ‘iatrogenic’ factors may contribute to the intractable nature of some medically unexplained symptoms.

Approaches to management

As well as the costs involved in managing this group of patients, frequent attendance and multiple investigation are associated with a poorer outcome (Reference Lin, Katon and von KorffLin et al, 1991; Reference Kouyanou, Pither and Rabe-HeskethKouyanou et al, 1998). There is now considerable evidence for the effectiveness of psychological therapies in medically unexplained symptoms, particularly cognitive—behavioural therapy, and studies have established the benefit of antidepressant drugs in syndromes such as atypical face pain and non-cardiac chest pain (Reference Smith, Rost and KashnerSmith et al, 1995; Reference Mayou and SharpeMayou & Sharpe, 1997). However, such treatments have not become widespread in the clinical setting for a number of reasons. First, the use of psychological treatments generally is limited to specialist centres with an interest in medically unexplained symptoms. Also, among medical professionals there remains an emphasis on viewing illness in wholly biological terms. A combination of anxiety about ‘missing something organic’, a lack of training in psychiatry and the continuing stigma attached to emotional problems make it far more acceptable to focus on physical investigations and treatment (Reference Smith, Rost and KashnerSmith et al, 1995; Reference Mayou and SharpeMayou & Sharpe, 1997). The willingness of patients to accept psychologically oriented treatments presents a further hurdle. Karlsson et al (Reference Karlsson, Lehtinen and Joukamaa1995) found high rates of depression and anxiety in a study of frequent attenders in primary care. However, the self-perceived need for psychiatric treatment was low, and very few received it.

Another approach focuses on strategies used in routine medical management that aim to reduce morbidity and emphasise rehabilitation rather than cure. Smith et al conducted a series of randomised controlled trials in primary care using this approach (Smith et al, Reference Smith, Monson and Ray1986, Reference Smith, Rost and Kashner1995; Reference Rost, Kashner and SmithRost et al, 1994). The intervention comprised a consultation letter sent to the physician of patients with a lifetime history of at least six medically unexplained symptoms. The letter made a number of recommendations for management, including: regularly scheduled appointments; brief physical examination at each visit, looking for signs of disease rather than relying on symptoms; avoiding investigations and hospitalisation unless clearly indicated; and understanding the somatic symptoms as an emotional communication. In patients of physicians receiving the intervention there was both a significant improvement in physical functioning and a reduction in medical care costs of over 30% (Reference Smith, Rost and KashnerSmith et al, 1995). Such measures have not been evaluated systematically in a secondary care setting but would be relatively simple to implement. Frequent attenders to a specialist clinic with medically unexplained symptoms could be identified by their previous consultations and referrals elsewhere, and a management plan devised. This would involve consultation with the same clinician consistently through the referral, which, as well as increasing patient satisfaction, has been shown to improve health outcomes (Reference van Dulmen, Fennis and Mokkinkvan Dulmen et al, 1995). The present study suggests that medical investigations are of limited value in this group of patients.

Previous studies have suggested a role for negative investigations in reassurance and, given the conflicting findings in the literature, further research is clearly warranted (Reference Sox, Margulies and SoxSox et al, 1981; Reference Hansen, Bytzer and BondesenHansen et al, 1991; Reference Potts and BassPotts & Bass, 1993; Reference Howard and WesselyHoward & Wessely, 1996). However, limiting the use of investigations to specific indications and avoiding repeated investigation remain key recommendations in the management of unexplained symptoms. These patients frequently are regarded somewhat disparagingly as the ‘worried well’ and, as a consequence, receive little interest from either psychiatrists or physicians. Given their use of health-care resources and the associated costs, improving the management of this group should be a priority.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

• In secondary medical care, almost one in five frequent attenders present repeatedly with medically unexplained symptoms.

-

• Frequent attenders with medically unexplained symptoms account for levels of service use and expenditure that are comparable with other frequent attenders, but the use and cost of medical investigations in this group are significantly greater.

-

• Strategies for managing this group of patients should include a focus on aspects of routine medical care as well as specific psychological interventions.

LIMITATIONS

-

• Data were collected retrospectively from medical records.

-

• The method used for identifying medically unexplained symptoms has not been validated.

-

• Overall costs in secondary care were calculated on a standardised basis and did not allow for individual variation.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by a grant from the NHS Executive National Research and Development Programme. We thank all of the NHS trusts who agreed to participate in this study and, in particular, the medical records staff who assisted in the retrieval of case notes. We also thank Dr R. Hooper for providing statistical advice and helpful comments on the paper.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.