Numerous studies have found that certain occupations such as medical professionals (including doctors, nurses, veterinarians), Reference Reinhart and Linden1-Reference Bartram and Baldwin5 farmers Reference Judd, Jackson, Fraser, Murray, Robins and Komiti6-Reference Browning, Westneat and McKnight8 and police Reference Violanti, Vena, Marshall and Petralia9-Reference Vena, Violanti, Marshall and Fiedler11 are at elevated risk of suicide compared with the general employed population. This could be explained by access to lethal means through work, as in the case of farmers reported to have taken their own life using firearms. Reference Booth, Briscoe and Powell12 Wider socioeconomic determinants and work-related factors, including exposure to stressful working conditions, could also influence the relationship between occupation and suicide. Reference Nishimura, Terao, Soeda, Nakamura, Iwata and Sakamoto13-Reference Ostry, Maggi, Tansey, Dunn, Hershler and Chen17 A problem common to many studies on this topic is that they are based on limited sample sizes, hindering statistical power to detect small effects. This article sought to examine the relationship between occupation and suicide across the full evidence base through systematic review and meta-analysis, thereby building on past narrative reviews. Reference Bedeian18,Reference Boxer, Burnett and Swanson19 In addition to offsetting statistical power limitations common to single studies, the review sought to investigate higher order patterning by occupational skill level or status. This was made possible through the classification of occupations according to a hierarchical internationally recognised coding framework. The main hypothesis of this study was that risk of suicide would vary by occupational skill level. The rationale for this hypothesis stems from past research demonstrating that psychosocial job stressors pattern by occupational skill level and that psychosocial job stressors are associated with mental illness. Reference LaMontagne, Keegel, Vallance, Ostry and Wolfe20

Method

Search strategy

The review was conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines (www.prisma-statement.org/). The search strategy targeted studies that reported information on suicide by occupation, published from 1950 until May 2012. Computer-based internet databases used for this search included: PubMed, Web of Science, Proquest and Scopus. The combinations of keywords used in the database search included: occupation* AND suicid*; work* AND suicid*; job AND suicid*. The search was also run using terms such as intentional self harm*. A secondary search examined the reference list of all retained articles. Both published and unpublished reports were considered in the review process. The initial data searches were conducted by A.D.M. Subsequent data checking and searches were overseen by M.J.S., J.P. and A.D.L, and mismatches in classification of studies were resolved by consensus.

Eligibility criteria and selection of studies

Only studies that had the key search terms in the abstract and suicidal behaviours as an outcome variable were considered. Conceptual articles were excluded. Following this, only articles that provided a clear assessment of occupation and that were in English were included. Qualitative studies were removed, leaving retrospective population-level studies, case-control studies, meta-analyses and systematic reviews. Preference was given to those studies able to provide information across representative populations (for example coverage across entire occupational groups), rather than smaller samples within specific populations. Research on suicide mortality (i.e. no articles on suicide ideation or attempts) was retained. All effect-size estimates were considered, including odds ratios (ORs), rate ratios (RRs), relative risks, proportionate mortality ratios (PMRs) and standardised mortality ratios (SMRs). Estimates needed to present either a standard error or 95% confidence intervals to be included in the meta-analysis.

Data extraction

Information extracted from each study included the location of the study, time period the study was conducted, author names, description of occupation, description of the comparison population (or control group), effect size for suicide mortality, confidence intervals and/or standard error.

Coding of occupation

Occupational grouping was assigned using major codes from the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) (version 2008). 21 These were: category 1 (managers, senior officials and legislators), category 2 (professionals), category 3 (technicians and associate professionals), category 4 (clerks), category 5 (service and sales workers), category 6 (skilled agricultural and fishery workers), category 7 (craft and related trades workers), category 8 (plant and machine operators, and assemblers), and category 9 (elementary occupations). Military occupations were coded 0 because these are unable to be classified according to skill level. Major groups were coded into four aggregate levels of skill, 22 from level 1 (the lowest skilled occupations) to level 4 (the highest skilled occupations). Military occupations were excluded from the aggregate skill level. Further information about the coding of occupations included in this review according to major ISCO grouping and aggregate skill level can be found in online Table DS1.

Statistical analysis

All effect sizes and confidence intervals were log-transformed. Where confidence intervals were unavailable, these were calculated using the standard error of the effect size. To assess the effect of occupational skill level on risk of suicide, separate random-effects meta-analyses were conducted for each occupational subgroup and skill level. The pooled subgroup results were presented on the exponential scale. The pooled effect size represents the risk of suicide among the subgroup of interest compared with the whole working-age population. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed through the I 2 statistic. Sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the impact of choosing different referent groups or populations, as well as to examine differences between males and females, and variation based on whether the study controlled for socioeconomic status (SES). Meta-regression was used to assess the extent to which statistical heterogeneity between studies were related to one or more characteristics of the studies. Reference Harbord and Higgins23 Funnel plots were used to assess the precision of estimates. Reference Sterne and Harbord24 A modified Egger's test was used to assess small study effects by performing a linear regression of the effect estimates on their standard errors, weighted by 1/(variance of the intervention effect estimate). Reference Harbord, Harris and Sterne25 All analyses were conducted using Stata 12.1 for Windows using the ‘metan’ suite of commands.

Results

A total of 1290 articles were identified using the search terms (Fig. 1). Initial scan of the title and abstract led to exclusion of duplicates, editorial and conceptual pieces. Review of the abstracts of the remaining 233 studies resulted in the exclusion of 45 case series and qualitative articles, and 29 articles on suicide attempt or ideation and mental illness (leaving only articles on suicide mortality). Following this, 159 full-text articles were read for inclusion. Review of all the reference lists of articles resulted in 21 additional articles being included from the reference lists of all articles retrieved. At the last stage of review, 146 articles were excluded because of incomplete reporting of either effects and/or occupations, leaving 34 eligible studies.

Quality assessment

The quality of included studies was guided by past published recommendations. Reference Sanderson, Tatt and Higgins26 Those deemed to be of acceptable quality can be found in online Table DS2 (as mentioned above, the grouping of occupations into the ISCO major (skill level) group category and aggregate skill-level groups can be found in Table DS1). Data used in all of the reviewed studies were based on official objective accounts of both occupation and mortality (for example standardised national coding of occupation, coronial determined causes of death). There were four nationally representative retrospective cohort studies included in the meta-analysis. Reference Agerbo, Gunnell, Bonde, Mortensen and Nordentoft27-Reference Notkola, Martikainen and Leino30 These had reliable coverage (information from the whole country) on both occupational information and mortality from cases and controls across an entire population. However, underreporting was generally not acknowledged or quantified and may bias the results of these studies. Further, the retrospective nature of the studies meant that information was drawn from past exposures. This means that measurement may be incomplete or relatively coarse, particularly when combined with the fact that these studies were developed to examine a number of health outcomes. Twelve studies were based on occupational-specific cohorts that followed people over time. Reference Vena, Violanti, Marshall and Fiedler11,Reference Baris, Armstrong, Deadman and Theriault31-Reference Tanaka, Nishio, Murakami, Mukai, Kinoshita and Mor41 The populations from which cases and controls were drawn in these studies are less likely to be representative than those nationally representative studies mentioned above. However, the completeness of recording of mortality outcomes and exposures may be more accurate in these studies because of their focus on health outcomes within specific and defined occupational groups. There were 18 case-control studies (information obtained from retrospective mortality databases) included in the meta-analysis. In these studies, deceased exposed (occupationally coded) individuals were compared with controls. Reference Browning, Westneat and McKnight8-Reference Violanti10,Reference Andersen, Hawgood, Klieve, Kolves and De Leo42-Reference Wong, Escobar, Lesage, Loyer, Vanier and Sakinofsky56 Some of the studies included in this meta-analysis adjusted for possible confounders such as SES, Reference Kposowa28,Reference Notkola, Martikainen and Leino30,Reference Kim, Hong, Lee, Kwak, Lee and Hwang46,Reference King, Threlfall, Band and Gallagher47,Reference Stack53-Reference van Wijngaarden55 but the majority did not. The highest quality studies were deemed to be those based on nationally representative cohort studies that were able to control for a range of possible confounders and had a control population drawn from the general population. Reference Agerbo, Gunnell, Bonde, Mortensen and Nordentoft27-Reference Notkola, Martikainen and Leino30

Characteristics of reviewed studies

Studies included in the review were conducted over a diverse range of time periods and locations. The majority of research on occupational suicide came from high-income areas of the world such as Canada, Reference Mustard, Bielecky, Etches, Wilkins, Tjepkema and Amick29,Reference Baris, Armstrong, Deadman and Theriault31,Reference King, Threlfall, Band and Gallagher47,Reference Wong, Escobar, Lesage, Loyer, Vanier and Sakinofsky56 the USA Reference Browning, Westneat and McKnight8-Reference Vena, Violanti, Marshall and Fiedler11,Reference Kposowa28,Reference Robinson, Petersen and Palu40,Reference Frank, Biola and Burnett44,Reference Liu and Waterbor48,Reference Miller and Beaumont50,Reference Sentell, Lacroix, Sentell and Finsuen51,Reference Stack53-Reference van Wijngaarden55,Reference van Wijngaarden, Savitz, Kleckner, Cai and Loomis57 and Europe. Reference Agerbo, Gunnell, Bonde, Mortensen and Nordentoft27,Reference Notkola, Martikainen and Leino30,Reference Brandt, Kirk, Jensen and Hansen32-Reference Rafnsson and Gunnarsdóttir39,Reference Fear and Williamson43,Reference Hytten and Weisaeth45,Reference Meltzer, Griffiths, Brock, Rooney and Jenkins49 There was one study each in Japan, Reference Tanaka, Nishio, Murakami, Mukai, Kinoshita and Mor41 Korea, Reference Kim, Hong, Lee, Kwak, Lee and Hwang46 New Zealand Reference Skegg, Firth, Gray and Cox52 and Australia. Reference Andersen, Hawgood, Klieve, Kolves and De Leo42 The earliest study was conducted in 1979 Reference Olsen and Sabroe37 and the latest study included was published in 2012. Reference Jansson, Alderling, Hogstedt and Gustavsson34 Ten studied suicide risk in both males and females, Reference Violanti10,Reference Mustard, Bielecky, Etches, Wilkins, Tjepkema and Amick29,Reference Tanaka, Nishio, Murakami, Mukai, Kinoshita and Mor41,Reference Andersen, Hawgood, Klieve, Kolves and De Leo42,Reference Kim, Hong, Lee, Kwak, Lee and Hwang46,Reference Meltzer, Griffiths, Brock, Rooney and Jenkins49-Reference Skegg, Firth, Gray and Cox52,Reference van Wijngaarden55 13 studies were based on male suicide Reference Browning, Westneat and McKnight8,Reference Vena, Violanti, Marshall and Fiedler11,Reference Baris, Armstrong, Deadman and Theriault31,Reference Brandt, Kirk, Jensen and Hansen32,Reference Jansson, Alderling, Hogstedt and Gustavsson34-Reference Mahon, Tobin, Cusack, Kelleher and Malone36,Reference Ponteva38,Reference Rafnsson and Gunnarsdóttir39,Reference Fear and Williamson43-Reference Hytten and Weisaeth45,Reference Wong, Escobar, Lesage, Loyer, Vanier and Sakinofsky56 and 2 studies analysed female suicide. Reference Hansen and Jensen33,Reference King, Threlfall, Band and Gallagher47 There were nine studies that examined all person suicides. Reference Violanti, Vena, Marshall and Petralia9,Reference Agerbo, Gunnell, Bonde, Mortensen and Nordentoft27,Reference Kposowa28,Reference Notkola, Martikainen and Leino30,Reference Olsen and Sabroe37,Reference Robinson, Petersen and Palu40,Reference Liu and Waterbor48,Reference Stack53,Reference Stack54 It was also possible for studies to report more than occupation (Table DS2). For example, Agerbo et al Reference Agerbo, Gunnell, Bonde, Mortensen and Nordentoft27 reported suicide mortality for 53 different occupational groups, whereas Browning et al, Reference Browning, Westneat and McKnight8 reported suicide among farmers in three different North American states. Jansson et al Reference Jansson, Alderling, Hogstedt and Gustavsson34 provided suicide mortality for one occupational group (chimney sweeps).

Fig. 1 Selection of studies for meta-analysis.

Various effect measures were used. As detailed in Table DS2, 16 studies used rate ratios (RRs), Reference Browning, Westneat and McKnight8,Reference Violanti, Vena, Marshall and Petralia9,Reference Vena, Violanti, Marshall and Fiedler11,Reference Agerbo, Gunnell, Bonde, Mortensen and Nordentoft27-Reference Notkola, Martikainen and Leino30,Reference Brandt, Kirk, Jensen and Hansen32,Reference Mahon, Tobin, Cusack, Kelleher and Malone36,Reference Ponteva38,Reference Andersen, Hawgood, Klieve, Kolves and De Leo42,Reference Fear and Williamson43,Reference Hytten and Weisaeth45,Reference Liu and Waterbor48,Reference Sentell, Lacroix, Sentell and Finsuen51,Reference Wong, Escobar, Lesage, Loyer, Vanier and Sakinofsky56 11 used SMRs, Reference Baris, Armstrong, Deadman and Theriault31,Reference Hansen and Jensen33-Reference Jarvholm and Stenberg35,Reference Olsen and Sabroe37,Reference Rafnsson and Gunnarsdóttir39,Reference Tanaka, Nishio, Murakami, Mukai, Kinoshita and Mor41,Reference King, Threlfall, Band and Gallagher47,Reference Meltzer, Griffiths, Brock, Rooney and Jenkins49,Reference Miller and Beaumont50,Reference Skegg, Firth, Gray and Cox52 3 used PMR measures Reference Violanti, Vena, Marshall and Petralia9,Reference Robinson, Petersen and Palu40,Reference Frank, Biola and Burnett44 and 4 studies used ORs. Reference Kim, Hong, Lee, Kwak, Lee and Hwang46,Reference Stack53-Reference van Wijngaarden55 As suicide is a rare event in a population, these measures of risk can be seen as comparable for the purpose of meta-analysis. Reference Greenland, Rothman and Greenland58 There were also a number of different referent populations used in studies on occupational suicide. One group of studies used an occupation at lower risk of suicide as a referent. Reference Kposowa28,Reference Andersen, Hawgood, Klieve, Kolves and De Leo42,Reference Frank, Biola and Burnett44,Reference Kim, Hong, Lee, Kwak, Lee and Hwang46,Reference Liu and Waterbor48,Reference van Wijngaarden55 A second group compared suicide in one occupational group to all other occupation groups except that of interest. Reference Violanti, Vena, Marshall and Petralia9,Reference Vena, Violanti, Marshall and Fiedler11,Reference Mustard, Bielecky, Etches, Wilkins, Tjepkema and Amick29,Reference Stack53,Reference Stack54 The last group included studies that used the general working-age population as a referent. Reference Browning, Westneat and McKnight8-Reference Vena, Violanti, Marshall and Fiedler11,Reference Mustard, Bielecky, Etches, Wilkins, Tjepkema and Amick29-Reference Hytten and Weisaeth45,Reference King, Threlfall, Band and Gallagher47,Reference Meltzer, Griffiths, Brock, Rooney and Jenkins49-Reference Skegg, Firth, Gray and Cox52,Reference Wong, Escobar, Lesage, Loyer, Vanier and Sakinofsky56

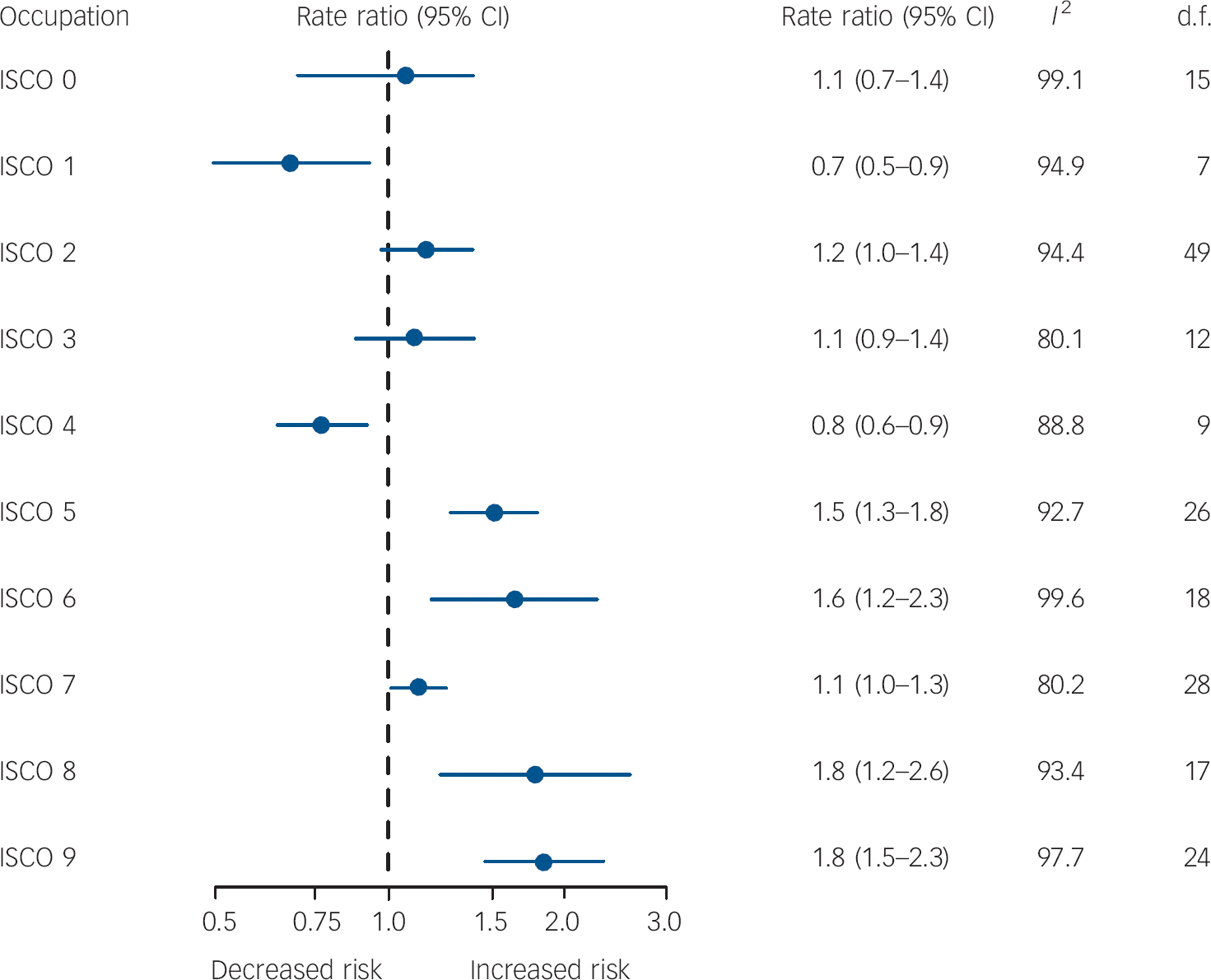

Results by ISCO categories

Individual results conducted for each of the nine ISCO categories can been seen in online Tables DS3-12, and Fig. 2 indicates the pooled results. The pooled RRs were interpreted as the risk of suicide in the category of interest compared with the working-age population (further subgroup analyses were conducted to assess the influence of different referent populations). The highest risk of suicide was apparent in the ISCO major category 9, which was comprised of ‘elementary’ occupations such as labourers and cleaners (RR = 1.84, 95% CI 1.46-2.33) and the major category 8 group, which represented plant and machine operators and ship's deck crew (RR = 1.78, 95% CI 1.22-2.60). There was also a particularly elevated risk among the ISCO major category 5 (RR = 1.52, 95% CI 1.28-1.80), which represented services such as police, and ISCO major category 6 (RR = 1.64, 95% CI 1.19-2.28) skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers. The lowest risk of suicide was seen in the highest skill-level group of managers (ISCO category 1, RR = 0.68, 95% CI 0.50-0.93) and clerical support workers (ISCO category 4, RR = 0.77, 95% CI 0.64-0.92). There was notable heterogeneity in sample size of each of the ISCO categories, reflecting differential research attention to certain occupations and skill levels. There were also notable differences in the number of studies included in each subgroup analysis, with ISCO 1 having only 8 studies (7 degrees of freedom), whereas ISCO 9 consisted of 25 studies (24 degrees of freedom).

Fig. 2 Results of meta-analysis of suicide by occupation with studies classified according to International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) 2008 major categories, Forrest plot.

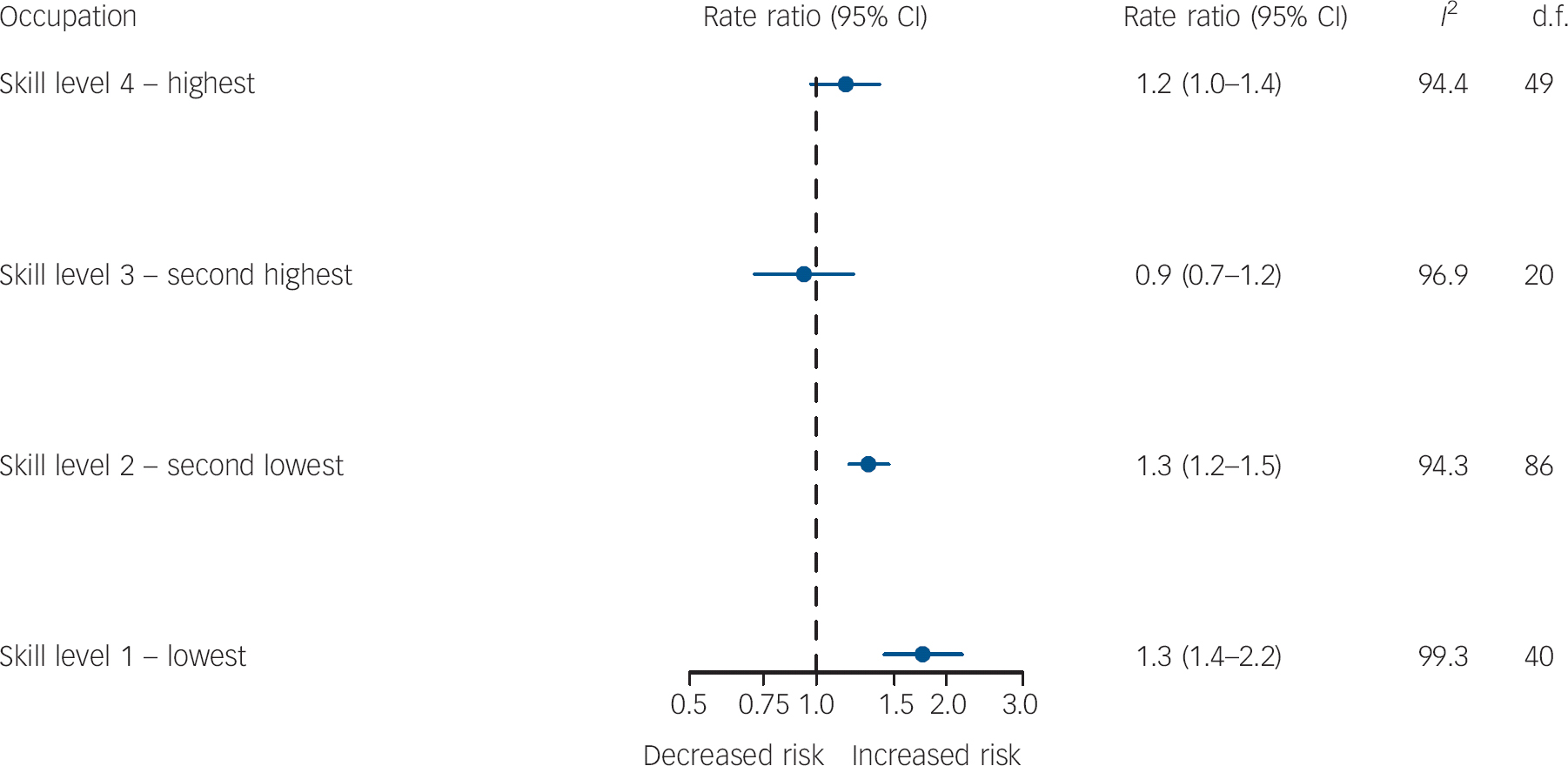

Results collapsed into four skill levels

There was no evidence of elevated suicide among skill levels 3 and 4 compared with the general working-age population. There did, however, appear to be a decreasing gradient from the lowest skilled occupations (skill level 1) to the second most skilled occupation (skill level 3) (Fig. 3). The lowest (RR = 1.76, 95% CI 1.42-2.17) and second lowest skilled occupations (RR = 1.32, 95% CI 1.19-1.47) had a higher risk of suicide than either the highest (RR = 1.16, 95% CI 0.97-1.40) or second highest skilled occupations (RR = 0.93, 95% CI 0.71-1.21).

Sensitivity analyses and meta-regression

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the effects of gender on occupational risk of suicide, although statistical power was limited by the reduced sample sizes (Table 1). Among males, only one of the four skill-level groups (level 2) was significantly different from an RR of 1.0. Risk was the highest in skill level 1 (i.e. the lowest skilled occupations) and decreased steadily to the highest skilled groups. For females, conversely, the highest skill-level group showed the highest RR; there was also, however, the suggestion of a gradient for occupations classified into levels 1 to 3 (with the greatest risk being in those occupations at the lowest skill level). The analysis for females was limited by a smaller number of studies reporting female suicide.

Fig. 3 Results of meta-analysis of suicide by occupation with studies classified according to International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) 2008 aggregate skill level, Forrest plot.

Those studies that compared the risk of suicide with the lowest-risk occupation generally showed stronger differences than those that used the employed population overall, or all other occupations (Table 1). These studies are better able to assess an occupational skill-level gradient in suicide, as they compare results to a distinct and often minimal risk occupational group.

A final sensitivity analysis was also conducted to assess whether the relationship between occupational skill level and risk of suicide was confounded by SES (Table 2). Contrary to expectation, effect size estimates for each skill level were elevated for studies with v. without SES adjustment (Table 2). This is likely connected to the methodological characteristics of the studies that adjusted for SES, which tended to be measured in relation to another occupational group at lower risk of suicide rather than the general population. Therefore, the increased risk may reflect the underlying characteristics of the reference population rather than the genuine influence of SES. In any case, limitations notwithstanding, there was no evidence of confounding by SES.

Heterogeneity

Results of the meta-regression analysis showed that the use of different referent groups explained about 16.7% of the between-studies variance. The use of a lower risk occupation as a referent group had a significantly greater effect on RR than the use of the whole working-age population as a referent. Socioeconomic status explained about 12.2% of the between-studies variance, and those studies that controlled for SES had a significantly greater risk of suicide by occupational skill-level group than those that did not. There were no significant effects found for gender on results. After controlling for gender and SES, results suggested that the effects of different referent groups remained a significant predictor of results. There were also differences in results based on study design, with case-control studies being significantly more likely to find greater effect sizes than either occupational cohorts or general cohort studies. However, there was no statistical difference related to the type of estimate used in the meta-analysis (possibly related to the fact that all effect estimates were transformed to be made comparable before analysis was conducted) or the location of the study. However, the year during which the study took place was found to significantly influence results, and accounted for 3.8% of between-study variance.

A funnel plot (online Fig. DS1) indicated that the majority of studies had small standard errors and RR estimates spanning from under one to approximately three. Observations with RR above three had larger standard error estimates, which may reflect small sample size or other limitations. The funnel plot also indicated possible publication bias as most studies report positive effects (i.e. occupations with greater risk of suicide than working populations) rather than negative effects. There was a smaller number of outlier studies with RRs above five and with standard errors above 0.5 to 0.4. Further investigation of possible bias using the modified Egger's test Reference Harbord, Harris and Sterne25 indicated that small study effects were evident in the results coded under ISCO major categories 1, 2, 4 and 5 (higher skill) but were not observable in those classified under ISCO major categories 3, 6, 7, 8 or 9 (lower skill).

Discussion

Main findings

This study confirms that certain occupational groups are at elevated risk of suicide compared with the general employed population, or compared with other occupational groups. At greatest risk were labourers, cleaners and elementary occupations (ISCO major category 9), followed by machine operators and ship's deck crew (ISCO major group 8). It is notable that there have been relatively few articles published on suicide in these groups, despite people employed in these jobs having a markedly higher burden of suicide than those in many other occupational categories. Significantly elevated risk was also apparent in farmers and agricultural workers (ISCO major group 6), service workers such as police (ISCO major group 5) and people in skilled trades (builders and electricians) (ISCO major group 7) compared with working-age populations. The lowest rates were seen in managers (ISCO major group 1) and clerical workers (ISCO major group 4). Results of this meta-analysis also indicated significant differences by skill level, with the lowest and the second lowest skilled professions being at particularly elevated risk. The second most skilled occupations had the lowest rates of suicide, but this was not significantly different from the working-age population.

Table 1 Sensitivity analyses, occupation and suicide studies classified according to International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) 2008

| Rate ratio (95% CI) | I 2, % | τ2 | d.f. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Males | ||||

| Skill level 1 | 1.30 (0.94-1.80) | 99.7 | 0.3732 | 13 |

| Skill level 2 | 1.19 (1.02-1.39) | 95.4 | 0.1219 | 22 |

| Skill level 3 | 0.89 (0.48-1.64) | 98.3 | 0.4642 | 4 |

| Skill level 4 | 0.94 (0.70-1.27) | 96.7 | 0.3834 | 18 |

| Females | ||||

| Skill level 1 | 1.14 (0.82-1.60) | 92.8 | 0.1929 | 8 |

| Skill level 2 | 1.16 (0.92-1.46) | 91.1 | 0.1652 | 20 |

| Skill level 3 | 0.64 (0.37-1.10) | 95.2 | 0.2458 | 3 |

| Skill level 4 | 1.28 (0.95-1.71) | 88.7 | 0.306 | 18 |

| Referent group | ||||

| Working-age population | ||||

| Skill level 1 | 1.02 (0.71-1.48) | 99.7 | 0.4150 | 11 |

| Skill level 2 | 1.06 (0.90-1.25) | 96.2 | 0.1654 | 29 |

| Skill level 3 | 0.72 (0.44-1.18) | 98.9 | 0.3091 | 4 |

| Skill level 4 | 1.01 (0.77-1.33) | 96.2 | 0.4253 | 25 |

| One other (lower risk) occupational group | ||||

| Skill level 1 | 2.78 (1.85-4.18) | 97.2 | 0.8212 | 20 |

| Skill level 2 | 1.53 (1.34-1.75) | 81.9 | 0.1667 | 51 |

| Skill level 3 | 1.07 (0.88-1.29) | 54.5 | 0.0688 | 13 |

| Skill level 4 | 1.34 (1.11-1.63) | 70.8 | 0.1221 | 19 |

| All other occupational groups | ||||

| Skill level 1 | 1.39 (1.54-1.68) | 94.8 | 0.0091 | 7 |

| Skill level 2 | 1.00 (0.89-1.13) | 44.9 | 0.0071 | 4 |

| Skill level 3Footnote a | 0.65 (0.56-0.75) | 0.0 | 0.000 | 1 |

| Skill level 4 | 1.32 (0.72-2.44) | 94.9 | 0.3455 | 3 |

a. Includes two observations, both from the same study.

Possible explanations for our findings

The greater risk of suicide in lower skilled occupational groups may be symptomatic of wider social and economic disadvantages, including lower education, income and access to health services. Reference Taylor, Page, Morrell, Carter and Harrison59 This explanation has been noted in a recent paper by Roberts et al Reference Roberts, Jaremin and Lloyd60 (unfortunately published after our analyses were completed and so it was not included in the meta-analysis), which also found that lower skilled occupations were at greatest risk of suicide in the UK, and that variation in suicide rates that was explained by occupational skill level increased significantly between 1979 and 2005. However, variation in SES disadvantage cannot explain the elevated suicide rates among those employed in highly skilled occupations, as these people are likely to be well paid and highly educated (as suggested in past research). Reference Agerbo, Mortensen, Qin and Westergaard-Nielsen61 In saying this, a limitation of this study is that it was unable to adequately assess the role of socioeconomic factors due to differences in the underlying methodological design of studies that did and did not control for SES. Most studies that did control for SES used another occupational group as a reference category (which led to greater differences in RR estimates), whereas most of those that did not control for SES used the entire working population as reference (which led to smaller differences).

Table 2 Sensitivity analyses, occupation and suicide studies classified according to International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) 2008 (continued)

| Socioeconomic status (SES) adjustment | Rate ratio (95% CI) | I 2, % | τ2 | d.f. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted for SES | ||||

| Skill level 1 | 2.28 (1.68-3.10) | 97.2 | 0.3851 | 18 |

| Skill level 2 | 1.51 (1.35-1.69) | 33.3 | 0.0155 | 19 |

| Skill level 3 | 1.92 (0.88-4.17) | 64.8 | 0.3000 | 2 |

| Skill level 4 | 1.53 (1.28-1.83) | 49.6 | 0.0454 | 13 |

| Not adjusted for SES | ||||

| Skill level 1 | 1.44 (1.09-1.90) | 99.5 | 0.4206 | 21 |

| Skill level 2 | 1.25 (1.11-1.41) | 95.4 | 0.3751 | 66 |

| Skill level 3 | 0.85 (0.65-1.12) | 97.1 | 0.3056 | 17 |

| Skill level 4 | 1.04 (0.84-1.29) | 95.4 | 0.3751 | 35 |

Access to lethal suicide methods through work may also explain some of the observed results, particularly the higher risk of suicide in ISCO categories containing farmers, police, military and medical professionals than other occupations. Reference Bedeian18,Reference Boxer, Burnett and Swanson19,Reference Stack62 An investigation of the methods used in suicide by occupational groups conducted in New Zealand Reference Skegg, Firth, Gray and Cox52 found that farmers were more likely to use firearms as a method to take their own life, whereas health professionals were more likely to overdose on drugs. However, those who died by suicide in the military did not use firearms in this study, despite these being readily available. This suggests that access to and familiarity with lethal suicide methods underpin some, but certainly not all, occupational suicides.

Alternatively, variations in suicide may reflect occupation-specific factors. There has been some research suggesting that the higher burden of suicide in agriculturally based occupations is connected to exposure to pesticides (aside from the intentional use of pesticides as a means of suicide). Reference Browning, Westneat and McKnight8,Reference Meltzer, Griffiths, Brock, Rooney and Jenkins49,Reference Lee, Burnett, Lalich, Cameron and Sestito63 A cohort study by Berlin et al Reference Berlin, Edling, Persson, Ahlborg, Hillert and Hogstedt64 found that people in occupations regularly exposed to solvents and toxins (for example house painters, mechanics, workers in the chemical-processing industry and printers) had between 1.5 and 2 times the risk of suicide compared with the general population. Explanations for these findings stem from research showing that workers exposed to certain pesticides have long-term neurological changes that may contribute to depressive symptoms. Reference Steenland, Jenkins, Ames, O'Malley, Chrislip and Russo65,Reference Stallones and Beseler66 The idea that pesticides increase the risk of suicide in certain occupations has been called into question in recent studies. Reference MacFarlane, Simpson, Benke and Sim67,Reference Beard, Umbach, Hoppin, Richards, Alavanja and Blair68 One possible explanation for these differences between studies is that there may have been declining exposure to chemicals over time. It is also possible that exposure is stronger in some areas than others, which would suggest that the geographical characteristics of studies is also important.

The quality of psychosocial working conditions may also explain variation in suicide by occupation. Although there have been only a few studies on the topic, those suggest an association between psychosocial job stressors (for example low job control, low social support, and high job demands) and suicide. Reference Nishimura, Terao, Soeda, Nakamura, Iwata and Sakamoto13-Reference Ostry, Maggi, Tansey, Dunn, Hershler and Chen17 A study by Ostry et al Reference Ostry, Maggi, Tansey, Dunn, Hershler and Chen17 found that psychological demands and social support at work were associated with both completed and attempted suicide in a cohort of sawmill workers. A cohort study with 9-year follow-up in Japan found a fourfold increase in the risk of suicide among men with low control at work. Reference Tsutsumi, Kayaba, Ojima, Ishikawa and Kawakami69 Psychosocial job stressors have also been found to be associated with intermediaries of suicide such as depression, Reference LaMontagne, Keegel, Louie and Ostry70,Reference Stansfeld and Candy71 and pattern by occupational skill level. Reference LaMontagne, Keegel, Vallance, Ostry and Wolfe20 Considering this, it is plausible that psychosocial job stressors have an influence on suicide mortality. Finally, it is impossible to rule out the possibility that certain occupations are at risk because of the underlying characteristics of the individuals employed in them. Reference Bartram and Baldwin5

Strengths and limitations

The main strengths of this paper lie in its classification of occupations using a standardised coding framework. Not only does this allow researchers the ability to compare like-occupations across studies, it also enables the investigation of higher-order patterning of occupation and suicide across the entire working population. At the same time, there were several methodological weaknesses. In some cases, available information on occupation was insufficient for unambiguous skill-group level classification. For example, those employed in the agricultural industry could be defined as either ‘skilled agricultural forestry and fishery workers’ (ISCO major category 6) or under ‘elementary occupations’ (ISCO major category 9). Unless specified by the article, occupations were classified under the first of these categories, which would tend to reduce occupational skill-level differences, biasing towards the null. Similarly, those employed in the construction and building industry could be classified in either ISCO major category 7 ‘craft and related trade workers’ or under ISCO 9 major category ‘labourers in mining, construction, manufacturing and transport’. In this case, classification of occupation was dependent on the amount of detail provided in the source article. With respect to the assessment of occupational skill-level differences, these problems were offset by collapsing of occupational skill level from nine to four groups. Limitations in the search strategy also may have meant that eligible studies may have been excluded or screened out of the meta-analytical review.

Another methodological weakness is that many studies on occupational suicide use effect measures such as SMRs and PMRs, which may obscure important effect modifiers such as SES. The differences in referent groups between studies is also a problem and there is noticeable variation between studies that used the general working population or another occupational group as a reference category (as seen in sensitivity analysis in Table 1). Reference Brugha, Matthews, Morgan, Hill, Alonso and Jones72 There may also be multiple comparisons between a control group and several occupational groups within a single study. We did not adjust for this as the only information available were log-transformed effect sizes for categorical outcomes (OR, RR, etc.) and their accompanying log standard errors/confidence intervals. If these multiple comparisons did influence the meta-analysis, we would expect results to be closer to null and produce more conservative findings. The different methodological characteristics between those studies that did and did not control for SES meant that we were unable to adequately assess the role of wider social and economic inequalities on the relationship between occupation and suicide.

There was also a large amount of heterogeneity between studies, which is likely because of inherent differences in how occupation was defined and classified, as well as connected to variation in when the study was conducted, and the social and geographical context of the study. At the same time, there were clear similarities between studies grouped with the major categories of ISCO 2008. This reflects the ongoing tension about whether the primary objectives of meta-analytical studies should be the estimation of an overall summary or average effect across studies, or the identification and estimation of differences between studies. Reference Greenland, Rothman and Greenland58

Implications

Although the meta-analyses was subject to a high degree of heterogeneity as a result of variation in study designs, referent populations and location of study, results indicate patterning in suicide mortality by occupational skill-level group. Future research is needed in order to validate these findings, and to investigate the high level of heterogeneity between studies. From a public health perspective, the results of this meta-analysis could suggest a need to prioritise intervention and prevention efforts for people employed in lower skilled jobs, particularly as these individuals may have limited access to the economic, social and health resources (as likely buffering or protective influences) available to those in higher skilled occupations. A particularly important (and understudied) area of work is the relationship between exposure to psychosocial job stressors and suicide. It would also be beneficial to understand the factors that protect some occupational groups from suicide compared with the general working population. Considering the workplace is increasingly recognised as a venue to screen and effectively manage mental health, Reference Barry, Jenkins, Barry and Jenkins73,Reference LaMontagne, D'Souza and Shann74 further research and investment into workplace suicide prevention efforts are necessary. Following best practice in workplace mental health promotion, Reference LaMontagne, Keegel and Vallance75 these interventions should aim to address job stressors and other work-related influences, while also building on factors that are protective against suicide by promoting positive mental health and help-seeking.

Funding

The National Health and Medical Research Council Capacity Building Grant in Population Health and Health Services Research (ID: 546248) provided salary support for A.D.M.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.