Adverse developmental experiences including abuse, deprivation and loss are well-established risk factors for psychosis. Reference Varese, Smeets, Drukker, Lieverse, Lataster and Viechtbauer1 Early adversity has an impact on later expression of psychosis by increasing stress sensitivity to later stressful life events. Reference Lataster, Myin-Germeys, Lieb, Wittchen and van Os2,Reference Lardinois, Lataster, Mengelers, van Os and Myin-Germeys3 Attachment theory Reference Bowlby4 has been successful in understanding adaptation to the long-term impact of adverse developmental experiences and stressful life events. Reference Fraley5 Attachment security is a significant building block to resilience and is linked to successful adaptation and recovery in the context of adversity. Reference Rutten, Hammels, Geschwind, Menne-Lothmann, Pishva and Schruers6 Attachment theory provides a developmental understanding of affect regulation, emerging from the evolutionary necessity for the infant to establish a safe haven (for distress) and secure base (for exploration). In adulthood, attachment security is characterised by freedom and autonomy to reflect on and explore painful feelings, and a valuing of interpersonal relationships. In adulthood, insecure attachment is reflected in two predominant strategies relating to adaptation and affect regulation. Preoccupied attachment is characterised by rumination, confusion and heightened emotional expression. Dismissing attachment is characterised by minimising and down-playing of attachment-related experiences, emotions, thoughts and memories. Dismissing attachment has been referred to as avoidant attachment. Reference Gumley, Taylor, Schwannauer and Macbeth7 A recent systematic review Reference Gumley, Taylor, Schwannauer and Macbeth7 of 21 studies comprising 1453 participants established the validity of attachment research in psychosis. Attachment security is associated with improved engagement with services, fewer interpersonal problems and reduced trauma. Attachment security is associated with fewer positive and negative symptoms and lower affective symptoms. However, the use of chronic, cross-sectional convenience samples limits the generalisability of findings. Our study was designed to provide a prospective study of attachment and its relationship with psychiatric recovery over time. The study aimed to establish the distribution of secure and insecure attachments in a cohort of individuals with first-episode psychosis, and to explore the relationship between attachment and recovery from positive and negative symptoms in the first 12-months following initiation of treatment. Our hypotheses were (a) that most individuals with a first episode of psychosis would be classified as insecure in their attachment; and (b) that controlling for symptomatology, duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) and psychiatric insight, greater attachment security would predict better recovery from positive and negative symptoms.

Method

The study was a 12-month prospective study of individuals with first-episode psychosis. Ethical (REC: 04/S0703/91) and research governance approval was granted before the start of the study. The study was conducted between 1 September 2006 and 31 August 2009.

Participants

Recruitment took place in National Health Service (NHS) mental health services in Glasgow and Edinburgh. All potential participants were approached for informed consent. Inclusion criteria were: (a) in-patients or out-patients with (b) first presentation to mental health services for psychosis, (c) DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizo-affective disorder, delusional disorder or bipolar disorder. 8 Members of the clinical teams providing their care identified individuals meeting these criteria and an invitation to participate in the research was extended by a member of the research team. Participation was voluntary and following receipt of informed and written consent participants were entered into the study.

Measures

All diagnoses were confirmed according to DSM-IV criteria 8 based on semi-structured interviews completed by research assistants. The two principal authors (A.I.G. and M.S.) then made diagnostic decisions at monthly research meetings. Severity of psychiatric symptoms was assessed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler9 a 30-item semi-structured interview for psychotic symptomatology. We examined two measures of outcome based on the PANSS scale: positive and negative symptoms, and PANSS assessments were conducted following entry to the service and at 6-month and 12-month follow-up. The PANSS assessments were rated by the principal authors (A.I.G. and M.S.), to establish interrater reliability at the outset of the study. We repeated checks on a 6-monthly basis to ensure continuing reliability over the course of the study. All estimates of reliability were above rho (ρ) = 0.80. For analysis of insight we utilised the insight item (G12) from the PANSS. A higher score on this item reflects less acceptance and insight into having a psychiatric illness and needing treatment. Ceskova et al Reference Ceskova, Prikryl, Kasparek and Kucerova10 have demonstrated the validity of the PANSS insight (G12) item in first-episode psychosis.

Information about onset and development of psychotic symptomatology Reference Beiser, Erickson, Fleming and Iacono11,Reference Skeate, Jackson, Birchwood and Jones12 was collected from the individual and (where possible) a carer or loved one. The DUP (interval between onset of psychotic symptomatology and onset of treatment) was calculated using the methods of Skeate et al. Reference Skeate, Jackson, Birchwood and Jones12 The test-retest reliability was reported as good (intraclass coefficient r = 0.96, P<0.01). Each participant was administered a semi-structured interview to ascertain the age at onset of any psychiatric symptoms and onset of psychotic symptoms. The DUP was calculated from the time of onset of the first psychotic symptoms of the presenting episode to the time of having received antipsychotic therapy for a period of 2 months, unless significant response to medication was achieved earlier. In cases where the first onset of psychotic symptoms was not linked with the presenting episode and there were one or more brief episodes of psychotic symptoms separated by long periods of remission only the periods of active psychotic symptoms were included in the calculation of DUP. In this study, estimation of DUP was assisted by diagrammatically charting it on a timeline specifying the interaction between life events, symptoms, social support and help-seeking. Timelines were constructed collaboratively and shared directly with participants to aid clarification and understanding. Timelines were shared for discussion at monthly research team meetings where DUP for each participant was agreed. Where exact dates were unavailable the middle date of the calendar month was taken as the date of onset.

The Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) Reference Hesse, Cassidy and Shaver13 is a semi-structured interview, consisting of 20 questions and probes, allowing categorisation of an adult individual’s state of mind with regard to attachment. Each interview is transcribed verbatim and coded for attachment status by coders trained and reliable in the AAI coding system (Version 7.1). Reference Hesse, Cassidy and Shaver13 Specifically, coherence of transcript (CohT) is an overall indication of the quality of the narrative throughout the transcripts both reflecting on the participant’s probable attachment experiences during childhood (for example loving, neglecting, rejecting), attachment-related experiences (including illness, separation, abuse and loss) and the participant’s state mind with respect to these experiences (i.e. secure, dismissing and preoccupied) as reflected in the transcript. The CohT is scored on a scale of 1 to 9, with higher scores indicating greater levels of coherence of discourse; this is the key index of attachment security, which is defined as the degree to which speakers portray their attachment experiences in a coherent and collaborative manner. Reference Hesse, Cassidy and Shaver13 Macbeth and colleagues Reference Macbeth, Gumley, Schwannauer and Fisher14 have demonstrated the validity of the AAI in a first-episode psychosis sample.

Transcripts are allocated one of three ‘organised’ categories: one ‘secure’ category - ‘freely autonomous and secure’ and two ‘insecure’ categories - ‘dismissing’ and ‘preoccupied’. Based on the AAI manual, individuals scoring 5 are allocated to the freely autonomous and secure attachment classification. Individuals classified as freely autonomous and secure tend to value attachment relationships, regard attachment experiences as influential, appear relatively independent and autonomous and appear free to explore both positive and painful thoughts and feelings. Individuals classified as dismissing tend to limit the influence of attachment-related experiences by denying, closing down or minimising these experiences. These individuals will often implicitly claim strength, normality and independence and provide a very positive description of early development, which is not substantiated by episodic memories. Individuals classified as preoccupied often appear confused. Discussions of attachment and other relational experiences are often prolonged, vague and uncritical or angry and conflicted and overwhelmed by trauma and loss. In addition, transcripts can be assigned a fourth category of ‘unresolved’ with regard to trauma and loss, where the coherence of an interviewee’s narrative breaks down in relation to discussions regarding trauma and loss. Where there was the presence of two or more contradictory attachment strategies a ‘cannot classify’ is assigned to these transcripts denoting a global breakdown in discourse and alternating use of attachment strategies. Reference Hesse15

Safeguards were included in the research protocol to ensure that the AAI was not conducted when participants were acutely psychotic or thought disordered. To enable interviewers and participants to establish rapport, lengthy interviews containing other baseline assessments including PANSS and DUP were always completed prior to the AAI. Since threats to validity of CohT arise from the presence of psychotic symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations, the CohT score can be adjusted to take account of these violations of narrative by assigning a coherence of mind (CohM) score. In our sample the association between CohT and CohM was r = 0.98. Interview stability has been reported as 90% at 3 months (kappa (κ) = 0.79). Reference Sagi, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Scharf, Koren-Karie, Joels and Mayseless16 After data collection for the study was completed, transcripts were coded by two researchers (A.M. and R.F.) with certified reliability in 3-category AAI classifications by Mary Main and Erik Hesse. Reference Hesse, Cassidy and Shaver13

Data analysis

We proposed linear multiple regressions incorporating two covariates (age and gender) and four predictors (corresponding baseline symptoms, DUP, baseline insight and CohT). For our analyses we used the CohT score as our measure of attachment security, with higher scores indicating greater security of attachment. The planned analyses consisted of two sets of linear multiple regressions in which all predictors and covariates were entered independently into the regression algorithm to avoid artificial inflation of estimated R 2. In addition to the regression, path analysis was also performed as part of our planned analysis. Path analysis is an appropriate way of approaching our hypothesis that attachment security, DUP and insight play a role in the symptomatic recovery of patients with first-episode psychosis. This method is well suited for testing interactions between independent variables and their effect on the dependent variable. Path analysis also enables the estimate of overall fit of the hypothesised models on the data. Owing to the relatively small sample size, the path models were constructed from observed variables.

We calculated the sensitivity of estimated effect sizes and power for these procedures using Sample Power 2.0 Reference Borenstein, Rothstein and Cohenet17 and Gpower 3.0 on Mac. Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner and Lang18 We conservatively estimated that a small effect size for the set of covariates and a medium effect size for the set of predictor variables would achieve power of 0.88 with a sample of n = 60. A sample n = 51 would give us a power of 0.80 using the same parameters. We conducted a sensitivity analysis of the sample size required to detect significant changes in R 2 assuming an effect size range of f 2 = 0.2-0.3. Estimation of a medium effect size was based on meta-analytic data on the strength of relationship between DUP and psychiatric symptomatology. Reference Marshall, Lewis, Lockwood, Drake, Jones and Croudace19 We also adopted a medium effect size to denote a clinically significant magnitude of effect to reflect health services practice and service design.

The regression analyses provided an overall estimate of the contribution of our predictors with clinical outcomes. For the regression analyses we transformed DUP using Log 10. For the regression models for PANSS positive and negative symptoms (at 6- and 12-months) we entered the covariates gender and age as well as the four predictors of respective baseline symptoms, Log10DUP, PANSS insight and CohT. Collinearity statistics for all linear regression models reported below were satisfactory, with tolerance generally above 0.1 and variance inflation factor (VIF: an indicator of severity of multicollinearity) statistics smaller than 10. All regression models were tested via bootstrapping with 1000 random samples; this method involved generating confidence intervals through a process of random resampling. The bootstrapped solutions confirmed the linear regression models.

Following the regression analyses, the path analyses provided an understanding of the interaction of these predictors to clinical outcomes. To test hypothesised direct and indirect effects we utilised structural equation modelling (SEM) using EQS version 6.1 on Windows Reference Bentler20 to test the path models. The SEM-based approach to testing mediation was chosen as it provides two key advantages over alternate methods: it tests the hypothesised parameters simultaneously and it provides an indication of the overall fit of the model. Reference Hayes22 The SEM-based approaches based on observed variables only is further more robust in smaller samples but can carry a conservative bias of models not converging. Reference Iacobucci23 Goodness of fit of all models was evaluated using the Satorra-Bentler robust fit statistics. The maximum likelihood χ2 statistic was corrected with the Satorra-Bentler robust χ2 statistic (S-B χ2) and the robust comparative fit index (RCFI). Reference Hu and Bentler24 Chi-squared is the most commonly used measure of model fit - a high chi-squared value with a significant P-value suggests a poor fit of the model to the data. The RCFI ranges from 0 to 1 with values greater than 0.90 indicating a good fit. The root mean square of approximation (RMSEA) Reference Browne, Cudeck, Bollen and Long25 is a measure of fit that takes into account a model’s complexity where a RMSEA of 0.05 or less indicates a good model fit.

Covariance SEM was utilised to examine the goodness of fit of two a priori models relating PANSS outcome variables at 12 months of positive and negative symptoms respectively to the predictor variables: DUP, PANSS insight, CohT and the respective baseline symptoms variable. For all path models we systematically tested direct and mediating effects of the main hypothesised mediating factors.

Results

Participant flow

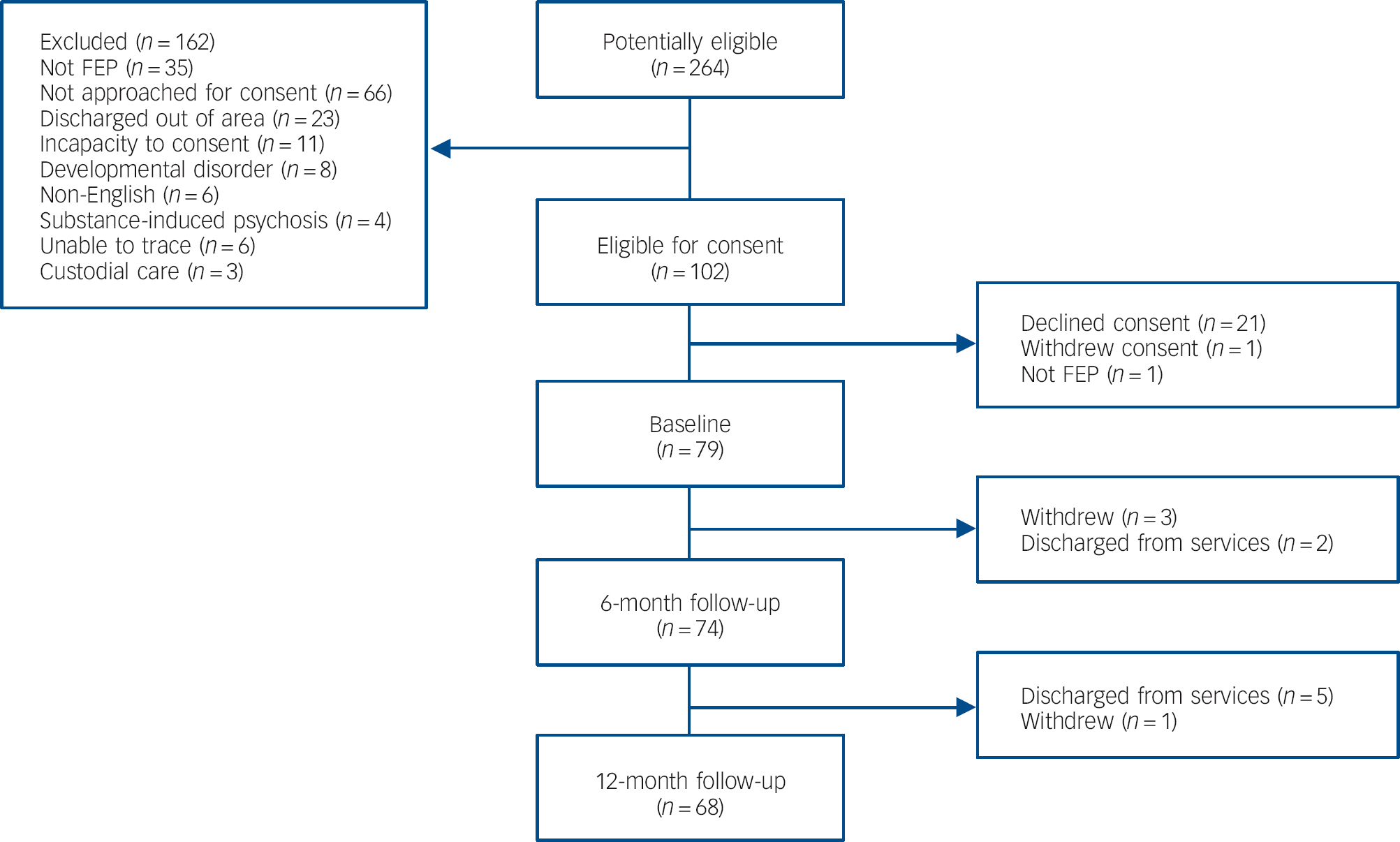

The participant flow is illustrated in Fig. 1. Of the 102 participants eligible for consent, 79 were entered into the study of whom 74 were followed up at 6 months and 68 at 12 months.

Fig. 1 Participant flow.

FEP, first-episode psychosis.

Basic demographic and clinical characteristics

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of our sample. The mean age of the sample was 24.64 (s.d. = 7.08) years; 54 (68.4%) were male, 38 (52.1%) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The sample had a median DUP of 16 weeks. We observed significant improvements in PANSS positive symptoms over 12 months (t = 10.91, P<0.001) and PANSS negative symptoms over 12 months (t = 2.6, P<0.012).

Table 1 Basic demographic and clinical characteristics

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | 79 |

| Male | 54 (68.4) |

| Female | 25 (31.6) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | 73 |

| Schizophrenia | 38 (52.1) |

| Schizophreniform disorder | 2 (2.7) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 8 (11.0) |

| Delusional disorder | 1 (1.4) |

| Bipolar disorder | 19 (26.0) |

| Other | 5 (6.8) |

| Admission at first episode, n (%) | 78 |

| Yes | 40 (51.3) |

| No | 38 (48.7) |

| Detained in hospital at first-episode psychosis, n (%) | 77 |

| Yes | 20 (26.0) |

| No | 57 (74.0) |

| Age at first contact, years: n | 79 |

| Mean (s.d.) median (IQR) | 24.64 (7.08) 22 (10.75) |

| Duration of untreated psychosis, weeks: n | 71 |

| Mean (s.d.) median (IQR) | 44.37 (73.96) 16 (60) |

| Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, n | 79 |

| Baseline, mean (s.d.) median (IQR) | |

| Positive | 20.82 (7.39) 20.5 (11) |

| Negative | 15.07 (8.31) 12 (10) |

| Insight | 3.17 (1.87) 3 (2.75) |

| Total | 74.43 (21.50) 71 (27.75) |

| 6 months, mean (s.d.) median (IQR) | |

| Positive | 11.57 (5.68) 10 (6) |

| Negative | 13 (6.62) 11 (8.5) |

| Insight | 2.46 (1.77) 2 (3.0) |

| Total | 52.88 (17.86) 48 (25.25) |

| 12 months, mean (s.d.) median (IQR) | |

| Positive | 10.7 (4.9) 9 (5) |

| Negative | 11.68 (7.05) 8 (9) |

| Insight | 2.18 (1.71) 1 (2.0) |

| Total | 47.78 (18.78) 42 (23) |

Attachment organisation

In our sample we were able to complete a total of 54 (63.4%) AAIs. Table 2 illustrates three-way (secure/autonomous, insecure dismissing, insecure preoccupied), four-way (including those unresolved for trauma and/or loss) and five-way (for the new and emergent cannot classify category) classifications: 68.5% were classified as insecure, of which 48.1% were dismissing and 20.4% preoccupied. We also show CohT scores for the three-way categorisation. Overall there was a statistically significant difference between the three groups (F(2,51) = 83.2, P<0.001), which was accounted for by statistically significant differences between the secure autonomous group and the insecure dismissing (P<0.001) and insecure preoccupied (P<0.001). There were no differences between the two insecure groups. Seventeen (31.5%) of the transcripts were classified as unresolved for trauma and/or loss. Six (11.1%) of the transcripts were categorised as cannot classify. Details of subcategories can be found in online Table DS1.

Table 2 Summary of Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) category for three-, four- and five-way analysis

| Three-way | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAI category | CohT, mean (s.d.) | n (%) | Four-way, n (%) | Five-way, n (%) |

| Secure: autonomous | 6.1 (1.2) | 17 (31.5) | 12 (22.2) | 12 (22.2) |

| Insecure: dismissing | 2.4 (0.9) | 26 (48.1) | 21 (38.9) | 20 (37.0) |

| Insecure: preoccupied | 2.3 (0.8) | 11 (20.4) | 4 (7.4) | 3 (5.6) |

| Unresolved | 17 (31.5) | 13 (24.1) | ||

| Cannot classify | 6 (11.1) | |||

CohT, coherence of transcript.

We found no significant correlation between CohT and PANSS conceptual disorganisation at baseline (r = –0.19), 6 months (r = 0.12) or 12 months (r = –0.07). We explored three-way attachment categorisation in relation to PANSS positive, negative, general symptoms and DUP. Multivariate analysis of variance revealed significant effects for three-way attachment categorisation for PANSS positive at entry (F = 4.66, P = 0.015) and PANSS positive at 6 months (F = 4.71, P = 0.014). Post hoc Sheffé analysis revealed that the insecure preoccupied group had higher positive symptoms at entry (P = 0.017) and at 6 months (P = 0.027) compared with the freely autonomous and secure group.

Predictors of psychiatric recovery and remission

Prior to formal analyses we examined correlations between predictor variables (Log10DUP, PANSS Insight, CohT), covariates (baseline PANSS positive and negative) and the key outcome variables at 12 months (PANSS positive and negative). All models were replicated for 6-month outcomes and were largely consistent with 12-month results. Table 3 shows these correlations, indicating significant associations between PANSS positive symptoms and PANSS negative symptoms and the key predictor variables insight, DUP and AAI CohT.

Table 3 Correlations between predictors, covariates and dependent variables

| 6-month follow-up | 12-month follow-up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PANSS positive | PANSS negative | PANSS positive | PANSS negative | |

| Predictors | ||||

| DUP (Log10) | 0.42Footnote ** | 0.24 | 0.26Footnote * | 0.13 |

| PANSS insight | 0.43Footnote ** | 0.36Footnote ** | 0.31Footnote * | 0.44Footnote ** |

| AAI coherence of transcript | −0.18 | −0.43** | −0.13 | −0.33* |

| Covariates | ||||

| Baseline PANSS positive | 0.26Footnote * | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.14 |

| Baseline PANSS negative | 0.26Footnote * | 0.60Footnote ** | 0.28Footnote * | 0.55Footnote ** |

PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; DUP, duration of untreated psychosis; AAI, Adult Attachment Interview.

** P<0.01

* P<0.05.

Recovery: positive symptoms

All final regression models are summarised in Table 4. For PANSS positive symptoms at 6 months the overall regression model accounted for 30.9% of the variance (F(50) = 3.28, P = 0.009). The significant predictor variables for positive symptoms at 6 months were DUP (β = 0.280, t = 2.14, P = 0.038) and insight as measured by the PANSS (β = 0.388, t = 2.34, P = 0.023). The AAI CohT was not a significant predictor. For PANSS positive symptoms at 12 months the linear regression model accounted for 27.6% of the variance (F(48) = 2.66, P = 0.028). In the regression model the only significant predictor variable for PANSS positive symptoms at 12 months was insight (β = 0.396, t = 2.28, P = 0.027). The AAI CohT was not a significant predictor.

Table 4 Predictors of recovery: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) positive and negative symptoms at 6 and 12 months

| Dependent and independent variables | β | t | P | R 2 (complete model) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PANSS positive at 6 months | ||||

| Age | 0.168 | 1.25 | 0.218 | 0.309Footnote ** |

| Gender | −0.060 | −0.46 | 0.626 | |

| Duration of untreated psychosis | 0.280s | 2.14s | 0.038Footnote * | |

| PANSS insights | 0.388s | 2.34s | 0.023Footnote * | |

| AAI coherence | −0.142 | −1.05s | 0.299 | |

| Baseline PANSS positive | −0.044 | −0.27s | 0.788s | |

| PANSS positive at 12 months | ||||

| Age | 0.148 | 1.05 | 0.299 | 0.276Footnote * |

| Gender | −0.174 | −1.28 | 0.208 | |

| Duration of untreated psychosis | 0.243 | 1.77 | 0.083 | |

| PANSS insight | 0.3962.28 | 0.027Footnote * | ||

| AAI coherence | −0.031 | −0.21 | 0.829 | |

| Baseline PANSS positive | −0.001 | −0.05 | 0.996 | |

| PANSS negative at 6 months | ||||

| Age | 0.095 | 0.928 | 0.359 | 0.611Footnote ** |

| Gender | 0.030 | 0.309 | 0.759 | |

| Duration of untreated psychosis | 0.183 | 1.85 | 0.070 | |

| PANSS insight | 0.131 | 1.17 | 0.245 | |

| AAI coherence | −0.245 | −2.30 | 0.026Footnote * | |

| Baseline PANSS negative | 0.522 | 4.62 | 0.001Footnote ** | |

| PANSS negative at 12 months | ||||

| Age | 0.125 | 0.978 | 0.339 | 0.403Footnote ** |

| Gender | −0.027 | −0.219 | 0.828 | |

| Duration of untreated psychosis | 0.159 | 1.27 | 0.210 | |

| PANSS insight | 0.312 | 2.20 | 0.033Footnote * | |

| AAI coherence | −0.307 | −2.28 | 0.028Footnote * | |

| Baseline PANSS negative | 0.141 | 0.985 | 0.330 |

AAI, Adult Attachment Interview.

** P<0.01

* P<0.05.

Recovery: negative symptoms

The linear regression model (Table 4) explained 61.1% of PANSS negative symptoms at 6 months (F(49) = 11.28, P<0.001). Significant predictor variables for negative symptoms at 6 months were AAI CohT (β = -0.245, t = -2.30, P = 0.026) and PANSS negative symptoms at baseline (β = 0.522, t = 4.62, P<0.001). For negative symptoms at 12 months the linear regression model overall accounted for 40.3% of the variance (F(47) = 4.62, P = 0.001). The predictor variables for negative symptoms at 12 months were baseline insight as measured by the PANSS (β = 0.312, t = 2.20, P = 0.033) and AAI CohT (β = –0.307, t = –2.28, P = 0.028).

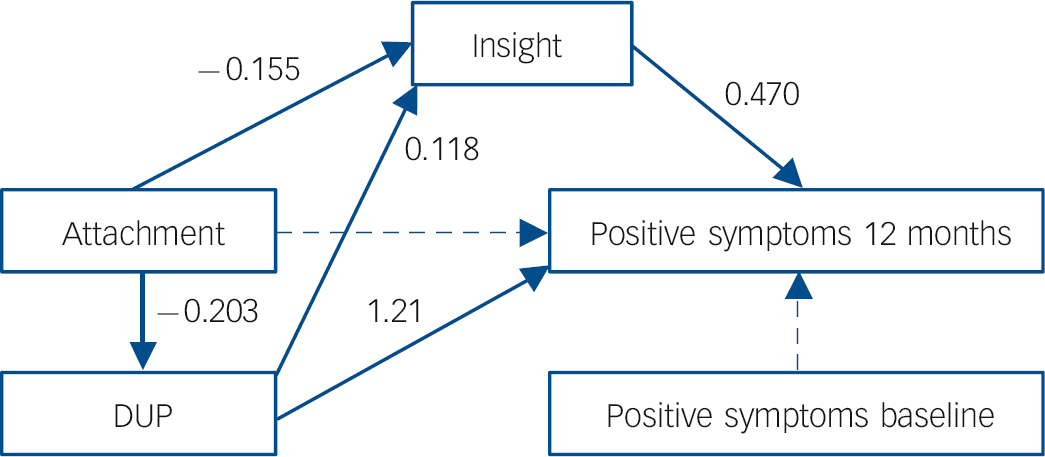

PANSS positive symptoms, path model

The hypothesised mediation model with associated fit indices is displayed in Fig. 2. This model fitted the data well (S-B χ2 = 13.82, P = 0.061; RCFI = 0.973; RMSEA = 0.051, RMSEA 90% CI 0.042-0.059). All direct and indirect paths were included in the analysis. Both PANSS insight at baseline and DUP had a direct effect on PANSS positive symptoms at 12 months. There were no significant direct effects of AAI CohT and baseline PANSS positive symptoms as suggested by the linear regression model. However, the path model clearly demonstrated a fully mediated relationship between attachment and positive symptoms at 12 months with insight and DUP acting as mediators, and a partial mediation of DUP and positive symptoms, with insight being a significant partial mediator, thus strengthening the association between DUP and symptoms at 12 months overall. It is also of interest to note that AAI CohT had a significant direct effect on DUP.

Fig. 2 Mediation model, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) positive symptoms at 12 months.

χ2 = 13.82 (P = 0.061); robust comparative fit index (RCFI) = 0.973; root mean square of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.05. DUP, duration of untreated psychosis.

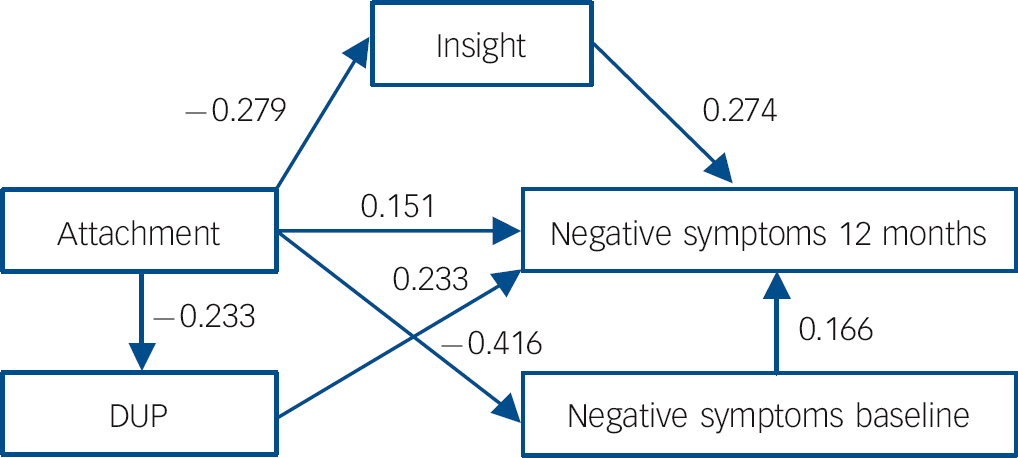

PANSS negative symptoms, path model

This model also fit the data well (S-B χ2 = 9.89, P = 0.094; RCFI = 0.926, RMSEA = 0.042, RMSEA 90% CI 0.037-0.046). The hypothesised mediation model with associated fit indices is displayed in Fig. 3. All direct and indirect paths were included in the analysis. Both PANSS insight at baseline and DUP had significant direct effects on negative symptoms; small significant effects could be observed for PANSS baseline negative symptoms and CohT. We observed clear mediation effects whereby CohT had strong effects on insight, DUP and in particular baseline negative symptoms, each of which directly affected PANSS negative symptoms at 12 months. The effect of CohT on negative symptoms at 12 months was therefore partially mediated by its effect on baseline negative symptoms, DUP and insight.

Fig. 3 Mediation model, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) negative symptoms at 12 months.

χ2 = 9.89 (P = 0.094); robust comparative fit index (RCFI) = 0.926; root mean square of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.04. DUP, duration of untreated psychosis.

Discussion

First, we aimed to establish the distribution of attachment representations in a cohort of individuals with first-episode psychosis. In line with our hypothesis, we found most participants were insecure in their attachment (n = 37, 68.5%); 26 (48.1%) were classified as dismissing and 11 as preoccupied (20.4%). Rates of unresolved attachment were 31.5% (n = 17). Significantly, most of our preoccupied group was also classified as unresolved for loss. These data are consistent with previous findings reported by MacBeth and colleagues Reference Macbeth, Gumley, Schwannauer and Fisher14 but differ from Dozier et al’s Reference Dozier, Stovall-McClough, Albus, Cassidy and Shaver26 finding that most of their chronic group were dismissing of attachment.

Second, we explored the relationship between attachment and recovery from positive and negative symptoms in the first 12 months. In terms of recovery from positive symptoms at 6 months we found that baseline PANSS positive and insight were significant predictors, however, at 12 months only insight remained significant. Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not find that attachment predicted positive symptom recovery. Previous studies have shown an association between attachment and positive symptoms, particularly for dismissing attachment. Reference Gumley, Taylor, Schwannauer and Macbeth7 However, these studies differ from the current study in that they use self-report methods, were conducted in chronic samples and tended to report bivariate associations. In addition, clinically important interaction effects between covariates tend to be masked in the linear regression models. In light of this, the findings of our positive symptoms path model are of interest. We found that increasing attachment security was associated with better insight at baseline and shorter DUP and the relationship between attachment and PANSS positive symptoms at 12 months was fully mediated by insight at baseline and DUP. These findings suggest that attachment security may exert an influence on the recovery from positive symptoms by acting on DUP and insight.

In terms of recovery from negative symptoms, attachment and baseline insight predicted recovery from negative symptoms at both 6 and 12 months. Path analyses demonstrated a small significant direct relationship between attachment and outcome of negative symptoms. In addition, the relationship between attachment and negative symptoms was partially mediated by insight and negative symptoms at baseline. Previous studies have also shown mixed results for the relationship between attachment and negative symptoms. Reference Gumley, Taylor, Schwannauer and Macbeth7 Unlike these studies we measured attachment using the AAI. The AAI provides an assessment of affect regulation during the discussion of salient interpersonal experiences. We note that the majority of our participants were insecure in their attachment and that almost half were dismissing. Attachment avoidance has been linked to the deactivation of positive and negative affect, interpersonal distancing, impaired mentalisation, avoidance of affect-linked autobiographical memories and a lack of trusting and confiding relationships. Reference Fraley27 Therefore the association with negative symptoms is of interest particularly in light of the lower levels of recovery in this outcome domain. One hypothesis would suggest that attachment processes may have a role in the unfolding of negative symptoms and that deactivation strategies linked to insecure attachment may be linked to the deactivation of positive and negative affect. Our findings in relation to positive symptom outcomes are consistent with this ‘affect regulation hypothesis’. Attachment security exerted an influence on positive symptom recovery via shorter DUP and higher insight. Attachment security is a marker for resilience and is characterised by openness to seeking help (shorter DUP) when distressed and greater awareness of thoughts, feelings and memories (improved insight). We also noted that 31% of our sample were unresolved for attachment and, further, 11% showed a global breakdown of attachment strategies (cannot classify). Given that both unresolved and cannot classify are closely linked to interpersonal trauma and loss, further research in this area would help clarify important relationships between trauma, attachment and outcome in psychosis. Reference Varese, Smeets, Drukker, Lieverse, Lataster and Viechtbauer1

We note that the neurobiology of attachment is increasingly understood through the role of dopamine and oxytocin circuitry. Reference Strathearn28 It has been proposed that difficulties in social cognition are underpinned by disruption in the amygdala and the dopamine and oxytocin circuitry linked to socio-emotional processing, which are also implicated in schizophrenia. Reference Rosenfeld, Lieberman and Jarskog29 Attachment theory therefore provides a framework to link models of affect regulation and adaption, impairments in social cognition and neurobiological mechanisms underpinning recovery following first-episode psychosis.

Limitations

Our study has some important limitations. We note that the choice of SEM for the investigation of indirect and mediating effects in a moderate sample like ours has some drawbacks. It offers a conservative method that forced use of observed rather than latent constructs, limiting the complexity of the associations that we were able to investigate. However, it also offered clear advantages in that we were able to assess the overall fit of the model as well as the strength of the associations and interactions between the variables. The analysis further highlights clearly significant and meaningful interaction effects that are masked in the linear regression models.

The direct relationship between attachment and negative symptoms does not allow us to infer causality. It may be that negative symptoms themselves impact on our measure of attachment security through impairments in memory functioning. Aleman and colleagues Reference Aleman, Hijman, de Haan and Kahn30 found a small but statistically significant association between negative symptoms and memory. This was across a range of memory domains including immediate and delayed recall of verbal and non-verbal behaviour and was not specific to measures of autobiographical memory relevant to attachment functioning. In contrast, there is increasing evidence to show that autobiographical memory impairment in schizophrenia is related to experience of trauma. Reference Shannon, Douse, McCusker, Feeney, Barrett and Mulholland31 In this model, some negative symptoms may arise from the attachment system’s regulation of negative affect through truncated recall of affect laden autobiographical memory related to attachment-related experiences that would also include loss and trauma experiences.

We did not utilise a self-report measure of attachment. However, Berry et al Reference Berry, Barrowclough and Wearden32 have noted that patients’ retrospective reports of attachment experiences may be subject to biases arising from the attachment system itself, meaning that individuals who are dismissing in their attachment are motivated to present their experiences as normalised and secure. Their comment that ‘the desynchrony between semantic and episodic portrayal of attachment-related experiences is used to assess attachment on the empirically robust Adult Attachment Interview’ overcomes the aforementioned problem and is a strength of this study.

We did not measure premorbid functioning in our analyses. In a systematic review of the literature, Reference Macbeth and Gumley33 premorbid adjustment had a modest effect on negative symptoms. However, the effects on positive symptoms were negligible. Future studies should focus on the relationships between premorbid social and academic functioning and its relationship to attachment and outcome.

We also note that individuals who declined consent may have been more likely to have difficulties related to their engagement with services. Therefore our sample may underestimate the prevalence of insecure and possibly insecure dismissing attachment in individuals with first-episode psychosis. It has been previously shown that clients with dismissing attachment pose particular challenges for engagement with keyworkers. Reference Gumley, Taylor, Schwannauer and Macbeth7 Insecure attachment (particularly dismissing) may be a key risk feature for the unfolding of problematical recovery, which expresses itself primarily through the individual’s interpersonal relationships including those with service providers. Consistent with this, Owens and colleagues Reference Owens, Haddock and Berry34 found that attachment anxiety and therapeutic alliance were significant predictors of emotion regulation problems in people diagnosed with schizophrenia. Further research is clearly merited in this area.

Clinical implications

Attachment insecurity and the associated diminished capacity to understand and reflect on one’s own thoughts and those of others (metacognition) Reference Macbeth, Gumley, Schwannauer and Fisher14 has been linked to impaired functioning Reference Lysaker, Dimaggio, Carcione, Procacci, Buck and Davis35 and is also associated with a history of sexual abuse. Reference Lysaker, Gumley, Brune, Vanheule, Buck and Dimaggio36 Brune Reference Brune37 has found that poorer levels of metacognition are related to more negative symptoms. The central finding of this study, that attachment is a consistent predictor of persisting negative symptoms, is important in the context of its applications to psychological treatments and models of mental healthcare for this group. We believe that this indicates a heightened importance of interpersonal processes and behaviours as a target for psychological therapies for psychosis. We note that the majority of our participants were insecure in their attachment organisation and that almost half of our participants were insecure/dismissing. As noted above, this particular attachment strategy has been linked to deactivation of positive and negative affect, distancing, impaired mentalisation, avoidance of thinking about autobiographical events and a lack of trusting and confiding relationships. Attachment as measured by the AAI provides an assessment of affect (dys)regulation that can contaminate interpersonal experiences; the association with negative symptoms is of interest particularly in light of the lower levels of recovery in this outcome domain. This has clear implications for current psychological treatment models, which tend to focus on levels of deficit rather than processes of adaptation to interpersonal challenge. Greater efficacy in psychological treatments for psychosis might therefore be achieved by a clear integration of interpersonal and metacognitive aspects of the client’s adaptation to emotionally salient interpersonal events. Attachment provides a framework to understand processes of affect regulation and recovery. In particular, we identify that those individuals with dismissing attachment may well be particularly vulnerable to problematic adaptation via impoverished reflexivity and avoidant coping. Reference Tait, Birchwood and Trower38

Funding

The authors acknowledge the financial support of NHS Research Scotland (NRS), through the Chief Scientist Office (CZH/4/295), and of the Scottish Mental Health Research Network. M.B. was partly supported by the NIHR Birmingham and Black Country Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Healthcare Research (CLAHRC).

Acknowledgements

The authors would also like to acknowledge the support of staff and service users in completing this project. The authors are grateful to four anonymous reviewers who provided detailed and constructive reviews throughout.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.