Over the past few decades, a considerable body of literature has focused on the question of whether media portrayals of suicide result in additional suicides, the so-called copycat effect. Reference Pirkis and Blood1,Reference Sisask and Värnik2 The risk of copycat effect has been reported to be strongest for sensationalist reports of celebrity suicides. Reference Niederkrotenthaler, Fu, Yip, Fong, Stack and Cheng3 With regard to fictional suicide stories portrayed in films, the evidence is more inconclusive, but some studies have reported increases in suicides following exposure to fictional stories, Reference Martin4,Reference Pirkis and Blood5 especially when the suicide method portrayed in a film was matched with the suicide rate by that particular method in the population. Reference Stack6 Some studies have suggested that identification with the protagonist of a media story may be a component in the pathway to copycat behaviour of violent media stimuli in general Reference Huesmann and Taylor7 and suicide portrayals in particular. Reference Fu and Yip8,Reference Niederkrotenthaler, Till, Kapusta, Voracek, Dervic and Sonneck9 Ecological studies are frequently used in this research area, but these studies have many limitations. Most importantly, it is not possible to determine whether individuals who took their own life following a suicide portrayal in the media were actually exposed to the story. Reference Pirkis and Blood5

Laboratory experiments provide an alternative to overcome this limitation, but have rarely been used to test the effects of portrayals of suicide on audiences. In a recent laboratory experiment, Reference Till, Vitouch, Herberth, Sonneck and Niederkrotenthaler10 personal suicidal ideation had a significant impact on how people coped with the film's content; specifically, the higher viewers scored for suicidal ideation, the more they tended to use films about suicide to develop ideas on how to go through life and address their own problems. This finding is consistent with previous research, which indicates that individuals with a history of suicide attempts or suicidal ideation are particularly vulnerable to engaging in suicidal behaviour following exposure to a suicide story in the media, Reference Cheng, Hawton, Chen, Yen, Chen and Chen11,Reference Zahl and Hawton12 and are more likely to report exposure to movies culminating in the protagonist's suicide. Reference Stack, Kral and Borowski13

The effects of media portrayals may also vary with the manner in which suicidal ideation is portrayed. Niederkrotenthaler et al Reference Niederkrotenthaler, Voracek, Herberth, Till, Strauss and Etzersdorfer14 found an association between sensationalist suicide reports and increases in suicide rates, but stories on individuals who contemplated suicide but then coped with adverse circumstances in a constructive manner were associated with a short-term decrease in suicide rates. This finding suggests that some media stories with suicidal content may even have a protective effect, called the Papageno effect. Reference Niederkrotenthaler, Voracek, Herberth, Till, Strauss and Etzersdorfer14 With more time spent in Western societies watching films than performing any other leisure activity, Reference Martin4,Reference Stack and Bowman15 and an increasing focus in mental health promotion on suicide awareness campaigns via the media, 16,17 further research is needed to investigate differences in the effects of films with regard to the outcomes of portrayed suicidal crises and the level of suicidal ideation of the audience. In the present study, we conducted a laboratory experiment to analyse the effects of three movies with different crisis outcomes on mood, depression, life satisfaction, self-worth, assumed benevolence of the world and suicidality. We also analysed how viewers identified with the protagonist of the respective film and assessed the impact of personal suicidal ideation on the observed film effects.

Method

Participants

The participants in this study were 95 individuals living in Austria (65 women and 30 men). They were recruited by means of posters, flyers and public announcements at facilities of the University of Vienna and the Medical University of Vienna and at other public venues (e.g. the Civic Centre) in Vienna, Austria, between January and April 2012. The participants' mean age was 27.32 years (s.d. = 10.43). High school graduation was the average level of education for both men and women. Women between 20 and 30 years of age and with high school and college degrees were over-represented in our sample compared with the total population in Austria.

Materials and procedure

We conducted a laboratory experiment with three groups of participants who watched a film featuring the portrayal of a suicidal crisis, each with a different outcome/ending. The films we selected were similar in terms of genre (i.e. drama) and all were Hollywood productions. Because research shows that film effects are influenced by the amount of aggression and violence shown, Reference Huesmann and Taylor7 we made sure to select only films that contained little or no on-screen violence as defined by Huesmann and Taylor. Reference Huesmann and Taylor7

Group 1 viewed the film ’Night, Mother (USA, 1986), an American drama that ends with the protagonist, Jessie, taking her own life. Jessie is a middle-aged woman with epilepsy who is unable to keep a job or drive. Her marriage has failed and her drug-addicted son has run away from home. One night, she calmly tells her widowed mother, with whom she lives, that she plans to end her life that very evening. Despite her mother's attempts to convince her that life is worth living, which are the main focus of the film but never result in any relief, the film ends with Jessie locking herself in her room and fatally shooting herself, off-screen. Regarding the amount of violence and aggression shown, this film contains several instances of non-physical aggression (e.g. insults, intimidation) and one case of mild physical aggression (i.e. shoving), as well as several instances of mild self-directed aggression by the protagonist.

Group 2 viewed the movie A Single Man (USA, 2009), an American drama that ends with the protagonist suffering a heart attack and dying. The protagonist, George, is a middle-aged English college professor who is unable to cope with his loss one year after the sudden death of his long-term partner. As he prepares to take his own life, he comes into contact with a student, Kenny, who shows interest in him. They fall in love and George overcomes his suicidal crisis. Shortly after, however, George dies of a heart attack. There is no violence or aggression in this film.

Group 3 watched the film Elizabethtown (USA, 2005), an American romantic comedy-drama that has a happy ending. Drew Baylor is the designer of the Späsmotica shoe, a hyped but flawed new product which, his boss informs him, will lose nearly a billion dollars to his company. Drew is fired for the mistake and is subsequently left by his girlfriend. Drew then plans an elaborate suicide. However, at the exact moment of his act of despair, his sister calls him to tell him that his father has just died and asks him to travel to Elizabethtown to retrieve his body for cremation. During his flight, he meets Claire, who changes his perspective on life. The film concludes with Drew falling in love with Claire and overcoming his crisis. No violence or aggression are portrayed in this film.

Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous, and the participants were randomly allocated to the groups (i.e. 31 participants were assigned to groups 1 and 2, respectively, and 33 participants were assigned to group 3). Questionnaires on mood, depression, life satisfaction, self-worth, assumed benevolence of the world and suicidality were completed before and immediately after the film. Identification with the protagonist was also measured after the film using a questionnaire.

For ethical reasons, only participants with suicidality and depression levels below established cut-off scores for the respective questionnaires were included. Four individuals were excluded from the study owing to suicidality or depression scores above the respective cut-off score. One individual decided to end participation in this study prematurely. The selection procedure reduced the original sample of 100 to 95 participants (n = 95). All participants were offered psychological counselling to help them cope with any distress resulting from exposure to the film or from answering questions on suicidality. The study took place at the Medical University of Vienna, Austria, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna and the Vienna General Hospital (study protocol 942/2011).

Measures

Mood subscale of the Affective State Scale

The mood subscale of the Affective State Scale Reference Becker18 uses responses to eight adjectives, such as merry or sad, scored on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 4 (highly), to provide scores on the participants' current mood (α = 0.86). We defined mood as a group of persistent feelings associated with evaluative and cognitive states that influence all future evaluations, feelings and actions. Reference Amado-Boccara, Donnet and Olié19

Erlanger Depression Scale

The Erlanger Depression Scale Reference Lehrl and Gallwitz20 uses eight self-report items (e.g. ‘I want to cry’) to assess symptoms of depression. Items are rated on a scale from 0 (completely wrong) to 4 (exactly right). Cronbach's alpha for this score was 0.66. Individuals with depression scores ≥17 were considered depressed and were excluded from the study.

Satisfaction with Life Scale

The Satisfaction with Life Scale Reference Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin21 is a five-item self-report measure used to assess life satisfaction (e.g. ‘I am satisfied with my life’). Items are rated on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Cronbach's alpha for this score was 0.84.

Self-worth subscale of World Assumptions Scale

The self-worth subscale of the World Assumptions Scale Reference Janoff-Bulman22 is a four-item self-report measure that generates a score for the participant's self-worth (e.g. ‘I am very satisfied with the kind of person I am’). Items are rated on a scale of 1 (disagree completely) to 6 (agree completely). Cronbach's alpha for this score was 0.72.

Reasons for Living Scale

The Reasons for Living Scale Reference Linehan, Goodstein, Nielsen and Chiles23 is a 48-item self-report measure that assesses beliefs and expectations about not committing suicide. It explores the (positive) adaptive reasons to refrain from suicide and the positive ways in which people address suicidal thoughts and feelings. Unlike other measures of suicidality, this scale has a solid theoretical base and, by focusing on strengths rather than weaknesses, assesses suicidality without the risk of inducing a depressive mood, Reference Range24 which has occasionally occurred with other scales. Reference Perlmuter, Noblin and Hakami25 Items (e.g. ‘I am afraid of the actual “act” of killing myself’) are rated on a scale of 1 (not at all important) to 6 (extremely important). The measures were transformed so that high scores indicated a higher manifestation of suicidal ideation (α = 0.83). Individuals with a suicidality score ≥106 were considered to be suicidal and excluded from the study.

Benevolence of the world subscale of the World Assumptions Scale

The benevolence of the world subscale of the World Assumptions Scale Reference Janoff-Bulman22 is a four-item self-report measure that generates a score for participants' assumed benevolence of the world (e.g. ‘There is more good than evil in the world’). Items are rated on a scale of 1 (disagree completely) to 6 (agree completely). Cronbach's alpha for this score was 0.79.

Cohen's Identification Scale

Cohen's Identification Scale Reference Cohen26 is a 10-items scale that measures an individual's identification with a specific character in a TV show or film (e.g. ‘While viewing the film I could feel the emotions character X portrayed’) answered on a five-point measure from 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree). Cronbach's alpha for this score was 0.91.

Data analysis

When computing the parameters, negative item scores were reversed. The items were then added to sum scores. Table 1 presents an overview of each parameter's mean and standard deviation before and after the movie screening. High scores indicate a high manifestation of the variable. For mood, high scores indicate a good mood. The scores of each dependent measure were subjected to a film group (’Night, Mother, A Single Man, Elizabethtown) test condition (pre-film, post-film) analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the F-test. Film group was a between-subjects factor, and test condition was a within-subjects factor in this analysis. Additionally, paired t-tests were performed to analyse the film-induced changes in the dependent measures in each film group.

Table 1 Indicators of subjective well-being in the audience before and after the film screening a

| Variable | Film | M1 | s.d.1 | M2 | s.d.2 | t-test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mood | Elizabethtown (happy ending) | 26.71 | 3.94 | 27.93 | 2.85 | 1.25 |

| A Single Man (death by natural causes) | 27.04 | 4.07 | 23.46 | 3.83 | −4.57*** | |

| ’Night, Mother (suicide) | 27.07 | 3.81 | 22.64 | 4.69 | −5.39*** | |

| Depression | Elizabethtown (happy ending) | 4.11 | 3.55 | 3.43 | 3.42 | −1.68 |

| A Single Man (death by natural causes) | 3.46 | 2.82 | 5.00 | 3.54 | 3.21** | |

| ’Night, Mother (suicide) | 2.93 | 2.85 | 4.25 | 3.33 | 2.86** | |

| Life satisfaction | Elizabethtown (happy ending) | 27.46 | 5.98 | 29.00 | 5.30 | 3.48** |

| A Single Man (death by natural causes) | 27.65 | 3.48 | 27.27 | 3.71 | −1.42 | |

| ’Night, Mother (suicide) | 28.21 | 5.41 | 28.82 | 4.91 | 1.74 | |

| Self-worth | Elizabethtown (happy ending) | 21.00 | 2.83 | 21.07 | 3.53 | − b |

| A Single Man (death by natural causes) | 20.54 | 2.78 | 20.31 | 3.43 | − b | |

| ’Night, Mother (suicide) | 20.75 | 3.45 | 21.68 | 3.07 | − b | |

| Assumed benevolence of the world |

Elizabethtown (happy ending) | 15.71 | 4.13 | 16.64 | 4.46 | 2.10* |

| A Single Man (death by natural causes) | 15.92 | 3.98 | 16.73 | 3.82 | 2.00 | |

| ’Night, Mother (suicide) | 16.11 | 3.86 | 16.46 | 4.11 | 0.72 | |

| Suicidality | Elizabethtown (happy ending) | 75.21 | 31.69 | 75.91 | 31.43 | 0.39 |

| A Single Man (death by natural causes) | 75.13 | 27.72 | 78.74 | 31.35 | 1.58 | |

| ’Night, Mother (suicide) | 71.45 | 24.04 | 73.23 | 27.60 | 0.76 | |

a. Values are means (M1) and standard deviations (s.d.1) before the film screening, and means (M2) and standard deviations (s.d.2) after the film screening; t-values from paired t-tests represent the change in the participants' indicators of subjective well-being

* P<0.05

** P<0.01

*** P<0.001 (two-tailed).

b. A t-test was only calculated for parameters with an overall F-test or interaction term ≤0.10.

To differentiate the effects on participants with lower v. higher suicidal tendencies, we split our sample into two groups by the median of the suicidality scores collected before the film (i.e. at baseline). Differences in identification with the protagonist of the respective film were assessed using an ANOVA with identification as the dependent variable and film groups as the factor. Associations between identification and baseline suicidality were estimated with Pearson product-moment correlations for each film group. Regression models with suicidality scores post-film screening as the dependent variable and baseline suicidality and identification as the independent variables were created and the interaction effects between baseline suicidality and identification were tested by introducing corresponding product terms into the models.

Results

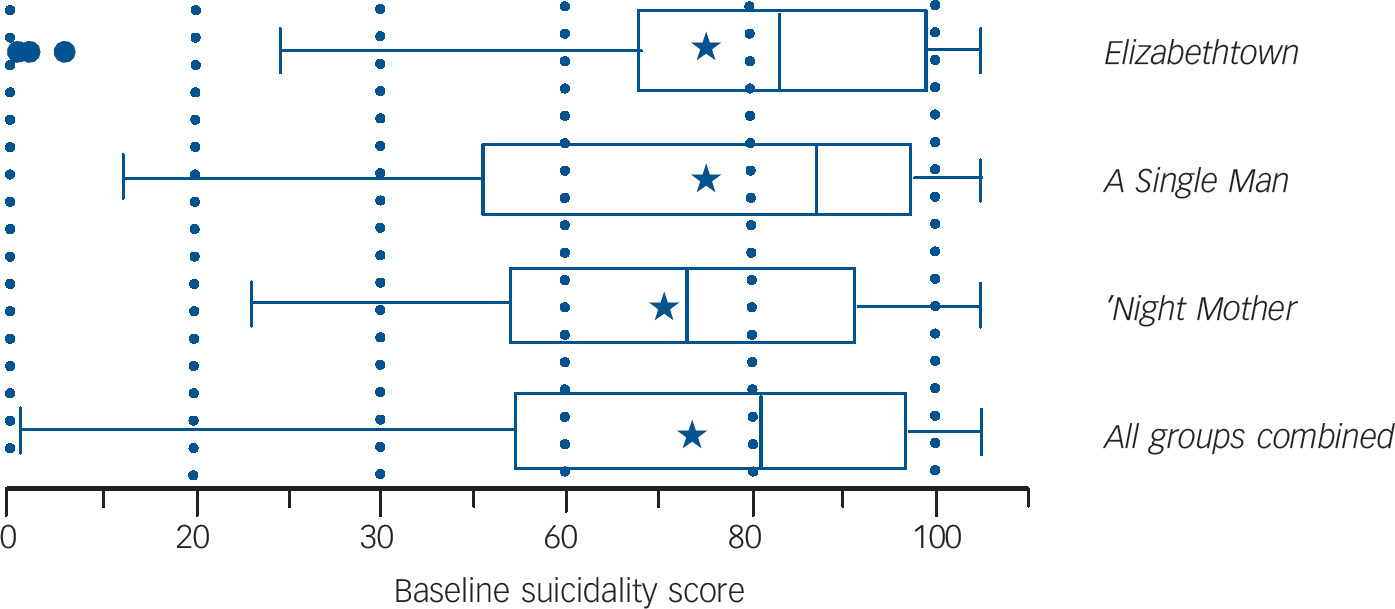

There was no significant difference with regard to baseline suicidality (i.e. suicidality scores before the film screening) among the viewers of the three films (F(2,95) = 0.18, P = 0.83). The distribution of the suicidality scores at baseline for each film group and for all groups combined is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Distribution of suicidality among viewers in the three film groups and among all viewers combined. Boxes represent values between the 25th and 75th percentiles; whiskers represent the upper and lower adjacent values; vertical lines represent the median; * represents the arithmetic mean; and • represents outliers.

Main effects and interactions

The analysis of the film effects revealed a significant film group × test condition interaction for mood (F(2,91) = 14.16, P<0.001), depression (F(2,92) = 7.49, P<0.01) and life satisfaction (F(2,91) = 7.17, P<0.01). With regard to assumed benevolence of the world, the ANOVA indicated a significant main effect (F(1,94) = 7.99, P<0.01), but no significant interaction (F(1,94) = 0.67, P = 0.51). Furthermore, there was no significant main effect (F(1,94) = 2.22, P = 0.13) and no significant interaction (F(2,94) = 1.44, P = 0.24) for self-worth. The main effect for suicidality was close to the boundary of statistical significance (F(1,95) = 2.73, P = 0.10) and there was no significant film group × test condition interaction (F(2,95) = 0.48, P = 0.61).

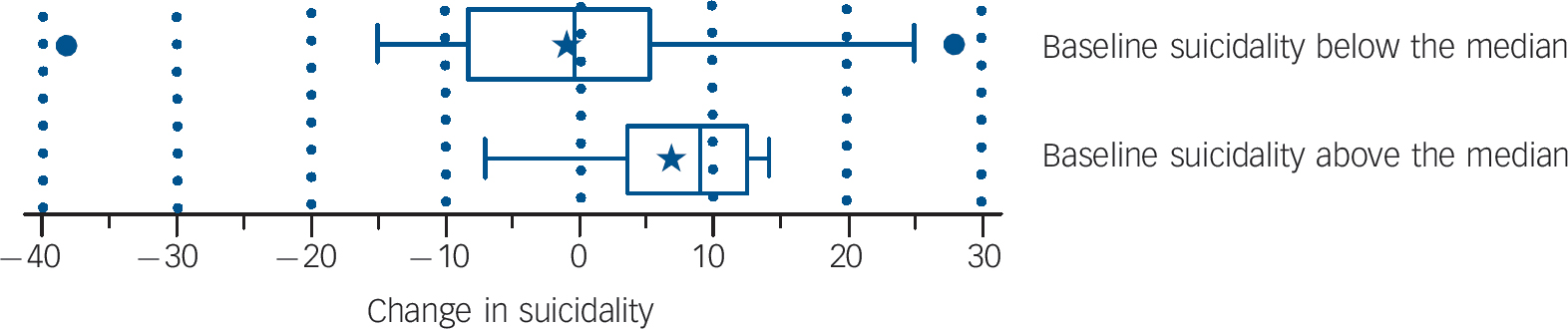

The impact of ’Night, Mother (film ending with the protagonist's suicide)

Evaluation of the interaction means and analyses of changes in the individual groups via paired t-tests indicated that there was a significant deterioration of mood and an increase in depression in this film group (see Table 1). When our sample was stratified, according to the suicidality score collected before the film screening (μ = 81), into one group with relatively lower suicidality (n = 49, μ = 55, interquartile range (IQR) = 36, min = 1, max = 81) and one group with comparatively higher suicidality (n = 46, μ = 97, IQR = 13, min = 83, max = 105), there was a significant deterioration of mood and an increase in depression among participants with lower suicidality, but not among those with higher suicidality. The individuals with lower suicidality also experienced a change in self-perception in terms of an increase in self-worth. In contrast, there was a significant increase in suicidality among viewers with higher suicidality (see Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Table 2 Indicators of subjective well-being before and after the film screening stratified for baseline suicidality a

| Lower suicidality | Higher suicidality | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Film | M1 | s.d.1 | M2 | s.d.2 | t-test | M1 | s.d.1 | M2 | s.d.2 | t-test |

| Mood | ET | 28.33 | 2.66 | 28.00 | 2.51 | −0.45 | 25.56 | 4.29 | 27.28 | 3.41 | 1.74 |

| SM | 27.36 | 2.59 | 22.93 | 3.81 | −5.88*** | 26.38 | 4.91 | 23.94 | 4.82 | −1.84 | |

| NM | 27.40 | 3.36 | 21.40 | 3.98 | −5.53*** | 26.64 | 4.20 | 24.64 | 4.80 | −2.00 | |

| Depression | ET | 2.80 | 2.57 | 2.40 | 2.06 | −0.84 | 5.78 | 4.56 | 4.22 | 3.90 | −1.49 |

| SM | 3.36 | 1.91 | 4.93 | 1.77 | 3.02* | 3.71 | 3.27 | 5.00 | 4.65 | 1.91 | |

| NM | 2.40 | 1.50 | 4.33 | 2.77 | 2.72* | 3.27 | 4.32 | 3.82 | 4.22 | 1.07 | |

| Life satisfaction | ET | 30.00 | 3.87 | 31.36 | 2.90 | 2.14 | 25.44 | 6.04 | 26.44 | 5.94 | 2.70* |

| SM | 28.00 | 3.19 | 27.64 | 3.25 | −0.75 | 25.82 | 5.45 | 25.38 | 6.19 | −1.21 | |

| NM | 29.15 | 4.76 | 29.35 | 4.45 | 0.59 | 27.27 | 6.02 | 28.45 | 5.32 | 1.92 | |

| Self-worth | ET | 22.20 | 2.27 | 22.47 | 1.92 | 0.53 | 19.67 | 2.79 | 19.61 | 3.73 | −0.09 |

| SM | 20.57 | 2.47 | 20.14 | 2.98 | −0.68 | 19.94 | 3.86 | 20.44 | 3.85 | 0.69 | |

| NM | 20.90 | 3.23 | 21.90 | 2.81 | 3.56** | 20.73 | 3.41 | 21.27 | 3.26 | 1.32 | |

| Assumed benevolence of the world |

ET | 16.93 | 3.75 | 17.80 | 3.57 | 1.71 | 14.28 | 3.66 | 15.00 | 4.52 | 1.31 |

| SM | 16.29 | 4.16 | 16.79 | 3.53 | 1.24 | 14.53 | 3.89 | 15.63 | 4.26 | 1.59 | |

| NM | 15.70 | 4.61 | 16.15 | 4.76 | 1.04 | 15.55 | 3.17 | 15.45 | 3.80 | −0.14 | |

| Suicidality | ET | 49.40 | 30.21 | 52.40 | 30.47 | 1.59 | 96.72 | 7.79 | 95.50 | 14.15 | −0.43 |

| SM | 49.00 | 19.29 | 51.71 | 21.23 | 1.11 | 96.65 | 7.03 | 101.0 | 17.64 | 1.18 | |

| NM | 57.30 | 16.95 | 56.35 | 16.96 | −0.29 | 97.18 | 7.71 | 103.9 | 11.53 | 3.13* | |

ET, Elizabethtown (happy ending); SM, A Single Man (death by natural causes); NM, ’Night, Mother (suicide).

a. Values are means (M1) and standard deviations (s.d.1) before the film screening, and means (M2) and standard deviations (s.d.2) after the film screening; t-values from paired t-tests represent the change in the participants' indicators of subjective well-being

* P<0.05

** P<0.01

*** P<0.001 (two-tailed).

Fig. 2 Distribution of change in suicidality among viewers of ’Night, Mother with lower suicidality and higher suicidality. Boxes represent values between the 25th and 75th percentiles; whiskers represent the upper and lower adjacent values; vertical lines represent the median; * represents the arithmetic mean; and • represents outliers.

The impact of A Single Man (film ending with the protagonist's death by natural causes)

There was a significant deterioration of mood, an increase in depression and an increase close to statistical significance in assumed benevolence of the world among viewers of A Single Man. The stratified analyses revealed that the deterioration of mood and the increase in depression were significant among participants with lower suicidality, but not among those with higher suicidality (Table 2).

The impact of Elizabethtown (film concluding with a happy ending)

Participants in this film group had significantly increased scores for life satisfaction and benevolence of the world after the film. The increase of life satisfaction was significant among viewers with higher suicidality and close to statistical significance among those with lower suicidality. There was no significant effect in the analyses of benevolence of the world stratified for baseline suicidality (Table 2).

Identification with the protagonist

Identification of study participants with the protagonist of ’Night, Mother, who takes her own life, was significantly lower than with the protagonist of A Single Man, who dies from natural causes (heart attack), or with the protagonist in Elizabethtown who overcomes his crisis (F(2,95) = 13.38, P<0.001). Identification with the protagonist of ’Night, Mother was significantly associated with baseline suicidality (r = 0.44, n = 31, P<0.05). The more suicidal the viewers were before the film screening, the more they identified with the main character of ’Night, Mother. Identification and suicidality were not significantly associated among viewers of A Single Man (r = −0.04, n = 31, P = 0.83) and Elizabethtown (r = 0.00, n = 33, P = 0.99).

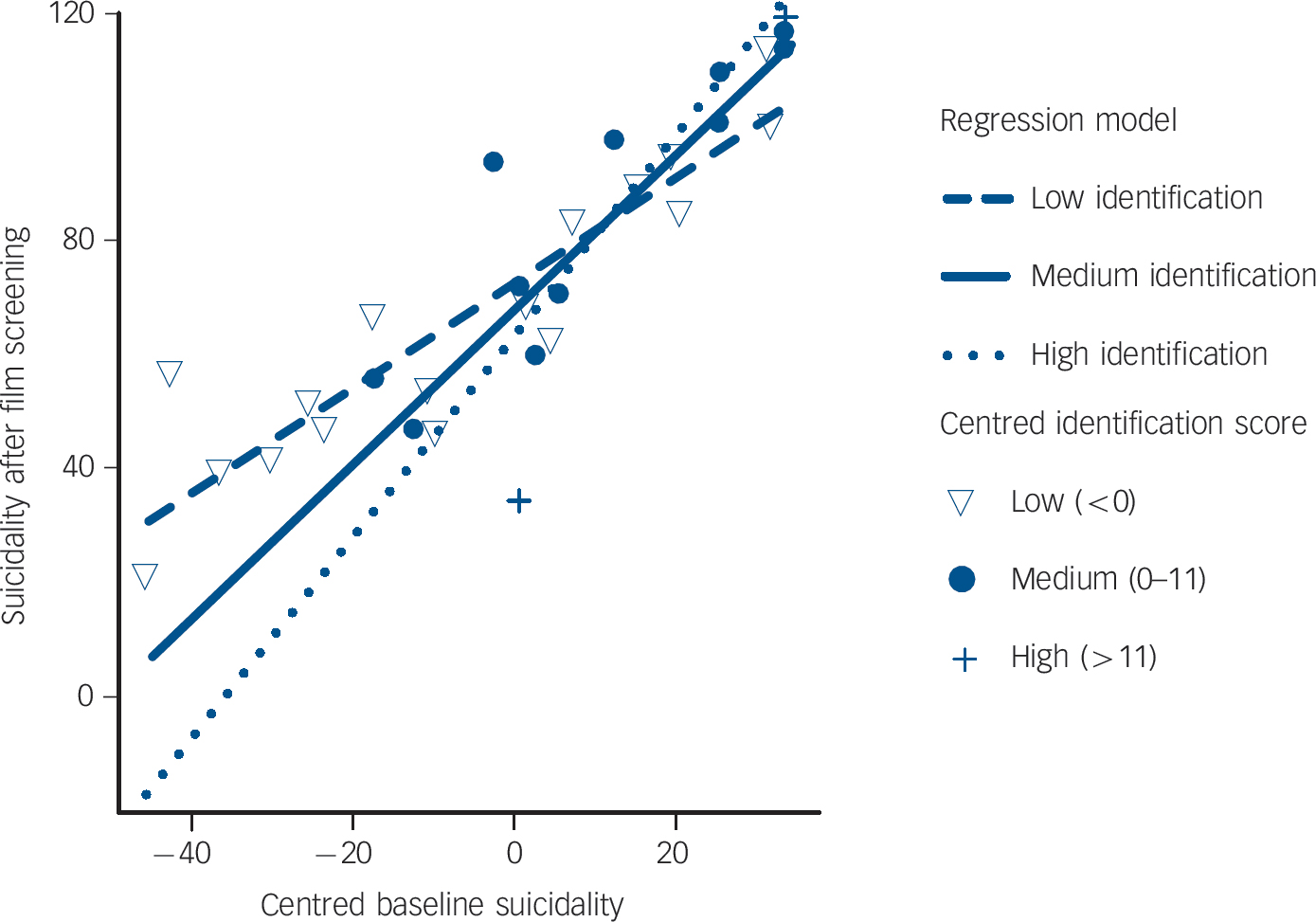

For the film ’Night, Mother, there was a significant interaction effect between identification and baseline suicidality on suicidality after film screening (B = 0.04, s.e. = 0.01, P<0.05) in the regression model (F(3,31) = 44.29, P<0.001, adjusted R 2 = 0.81). The interaction effect is shown in Fig. 3. There was no significant interaction term for the films A Single Man (B = −0.01, s.e. = 0.01, P = 0.59) and Elizabethtown (B = 0.00, s.e. = 0.01, P = 0.79).

Fig. 3 Interaction effect between identification and baseline suicidality on post-screening suicidality for the film ’Night, Mother. Lines show the regression model for three illustrative values of identification (low, medium and high). For centred baseline suicidality and identification, scores of 0 represent the arithmetic mean. The identification scores were divided into three equally sized intervals (low, medium and high) and the model was evaluated at the interval c points.

Discussion

The impact of ’Night, Mother (film ending with the protagonist's suicide)

The results of the present study show that the viewers of this film, which ends with the suicide of the protagonist, were significantly sadder, unhappier and more depressed after the film screening than they were before the screening. The viewing of this movie led to a significant deterioration of viewers' mood and an increase in depression scores. This finding is generally concordant with affective disposition theory, which proposes that an outcome that victimises protagonists and portrays their downfall is deplored by viewers. Reference Zillmann27 Previous studies demonstrated a similar deterioration of mood after the screening of movies ending with the protagonist's suicide. Reference Till, Niederkrotenthaler, Herberth, Vitouch and Sonneck28,Reference Till, Niederkrotenthaler, Herberth, Voracek, Sonneck and Vitouch29 The finding that a significant deterioration of mood and increase of depression scores was found only among viewers with lower suicidality but not among those with higher suicidality in the present study is consistent with the concept of affective constriction. Suicidality can be understood as a transient psychological constriction of perception, intellect and affect. Reference Ringel30,Reference Shneidman31 The affective constriction found in suicidal individuals is reflected in a diminution or cessation of feeling. Reference Shneidman31 The resulting reduction in affective resonance and variability may prevent any change in the affective state of a suicidal individual when exposed to a film ending with the protagonist's suicide. Reference Ringel30

While the deterioration in mood was only seen in participants with lower suicidal tendencies, those who recorded suicidal ideation scores above the median of the sample before the film screening experienced an increase in suicidal ideation after the film screening. This finding is consistent with the concept of perceptual constriction, Reference Ringel30,Reference Shneidman31 which emphasises that suicidal individuals tend to be occupied with thoughts about suicide and death, and may not be able to distance themselves from the dramatic suicidal development portrayed in a movie that culminates in the protagonist's suicide.

Identification with the protagonist may play a relevant role in the increase in suicidality scores among vulnerable individuals. As indicated by the interaction effect between vulnerability as indicated by baseline suicidality and identification with the protagonist, it is those individuals who identify with the character portrayed who are particularly prone to increases in suicidal ideation. Individuals with comparatively higher suicidality who identify with the protagonist may find the protagonist of a suicidal film more appealing and more realistic Reference Huesmann and Taylor7 and therefore more relevant to their own lives in comparison with individuals with lower suicidality or individuals who do not identify with the protagonist. Based on the finding that viewers of ’Night, Mother, who showed higher baseline suicidality and more strongly identified with the protagonist, formed the group who experienced the strongest increase of suicidality scores when exposed to the movie, extreme caution is then necessary when other suicidal individuals are exposed to suicide in the media, because those individuals who particularly identify with the suicidal protagonist may respond with stronger increases in suicidal ideation.

The differences in film effects with regard to viewers' baseline suicidality are further highlighted by the effect of ’Night, Mother on the viewers' self-worth, which increased in the group with lower suicidality scores but did not change in the group with higher suicidality scores. A possible explanation for this finding can be found in Festinger's social comparison theory, Reference Festinger32 which suggests that people tend to evaluate themselves by comparing themselves with other individuals. The confrontation with the hopeless situation portrayed in the suicide film (’Night, Mother) may have produced some type of ‘contrast effect’ Reference Till, Niederkrotenthaler, Herberth, Vitouch and Sonneck28 that led to a more positive self-evaluation in the group without any signs of suicidality. This conclusion is consistent with the findings of Mares & Cantor, Reference Mares and Cantor33 who suggested that people use sad movies to cope with negative life experiences. Viewers with low suicidality seem to be capable of reaching a positive conclusion about their own lives when exposed to the tragic outcome of the protagonist.

The impact of A Single Man (film ending with the protagonist's death by natural causes)

Notably, a significant deterioration of viewers' mood and an increase in depression were also recorded in individuals who watched the film where the protagonist died from natural causes (heart attack) (A Single Man). The fact that this film ends with the main character's natural death likely accounts for the negative emotional reactions in this group, which is concordant with affective disposition theory. Reference Zillmann27 Importantly, there was no film-induced change in suicidality among viewers with lower or higher baseline suicidality, which suggests that more suicidal individuals are not negatively affected by portrayals of natural death.

The impact of Elizabethtown (film concluding with a happy ending)

Viewers of the film Elizabethtown, which ends happily, did not experience any negative film effects, but reported an increase in life satisfaction and assumed benevolence of the world. These effects may be due to the kind and benevolent portrayal of the world that frames the protagonist's coping with his personal crisis in this film. While these findings suggest a possible beneficial short-term effect of a media portrayal of successful coping in adverse circumstances, Elizabethtown did not seem to affect the most important outcome variable, namely, suicidality. Based on the present findings, we can conclude that the media portrayal of successful coping when facing adverse circumstances increases life satisfaction, which is an important suicide-protective factor, and this increase is particularly pronounced among more vulnerable individuals.

Limitations

Clinically suicidal individuals with a suicidality score ≥106 Reference Linehan, Goodstein, Nielsen and Chiles23 were excluded from participation in our study for ethical reasons, and the generalisability of the results beyond individuals with moderate depression or suicidality scores to this high-risk group remains unclear. Suicidal individuals may be particularly prone to increases in suicidal ideation after exposure to media content culminating in a suicide. Reference Cheng, Hawton, Chen, Yen, Chen and Chen11,Reference Zahl and Hawton12 Of note, suicidality has often been described within a ‘continuous model’, which implies that a core difference between low and high suicidality is increased internal pressure towards suicidal action. Reference Wolfersdorf, Mauerer, Franke, Schiller and König34 A further study limitation is that the films used in this analysis, while similar in terms of genre and portrayal of on-screen violence, differed with regard to many other characteristics beyond the portrayal of suicidality, such as sound, light and characters portrayed. Factors such as audio and visual stimuli, Reference Boltz35,Reference Roy, Mailhot, Gosselin, Paquette and Peretz36 as well as camera positions, Reference Cohen26 have an impact on identification with the protagonist and affective responses. Reference Huesmann and Taylor7 Thus, differences across film groups may be based on factors other than the portrayal of suicidality. However, the stylistic elements of a film, such as the soundtrack, usually support the content of a film, Reference Boltz35 particularly in mainstream movies as used in the present study. A further limitation is that our sample was not representative of the general public. Young female student populations were over-represented in the study sample. Previous research suggested that the suggestive effects of suicide portrayals may be most relevant to young individuals. Reference Schmidtke and Schaller37 However, more research is necessary to evaluate these effects in different sociodemographic groups. Finally, group sizes were relatively small, resulting in limited statistical power. We therefore cannot rule out the presence of unidentified associations in the subgroup analyses.

Implications for practice, policy and research

The finding that suicidal ideation increased among viewers of ’Night, Mother, who experienced comparatively higher suicidality, is of great relevance to suicide research and prevention as it highlights the need to exert great caution when suicidal individuals are shown a film that culminates with the protagonist's suicide. The finding also highlights that any suicide awareness material featuring a completed suicide needs to be tested for vulnerable individuals as individuals with some degree of baseline suicidality seem to react in a different way to the portrayal of a suicide compared with psychologically stable individuals. Media guidelines for reporting on suicides, which are currently primarily aimed towards text-based media, 38 need to be adapted for suicide portrayals in films and television programmes, and guidance on the portrayal of suicidality should be included in guidelines for the development of mental health awareness campaigns. 39

Importantly, the impact of suicide-related film content seems not only to differ with regard to the viewers' vulnerability to suicide and their identification with the suicidal character, but also with regard to how the suicidal crisis is portrayed. Consistent with several ecological studies on the potential impact of news reports on suicide, Reference Cheng, Hawton, Chen, Yen, Chen and Chen11,Reference Pirkis, Burgess, Francis, Blood and Jolley40 this study highlights that not every suicide-related media portrayal results in an increase of suicidal tendencies in the audience. The portrayal of the successful mastering of a crisis in particular may have some positive impact on the audience, and further research using individual data is necessary to determine the media characteristics that enhance the protective effects of suicide-related media portrayals in accordance with the Papageno effect. Reference Niederkrotenthaler, Voracek, Herberth, Till, Strauss and Etzersdorfer14

The present study provides a rich basis for further research in this topic. Future studies using larger sample sizes are necessary to investigate pathways between baseline vulnerability, identification and film effects, and to investigate differences with regard to gender and age groups. Particularly, research on the impact of suicide portrayals on individuals at risk is needed, provided that these studies are conducted under close supervision in accordance with ethical considerations. Studies with a longer follow-up to investigate possible long-term effects of media portrayals seem warranted. Films that are identical with regard to characteristics other than the outcome of the crisis being portrayed are needed to disentangle specific characteristics that may alter the effects of the stimulus material. Further, the impact of suicide portrayals may vary with characteristics such as film genre (e.g. horror films v. dramas), or with the protagonist's social status (e.g. portrayal as a hero v. villain), Reference Niederkrotenthaler, Till, Kapusta, Voracek, Dervic and Sonneck9,Reference Stack and Bowman15 and the impact of these characteristics on film effects requires further scrutiny.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.