Background

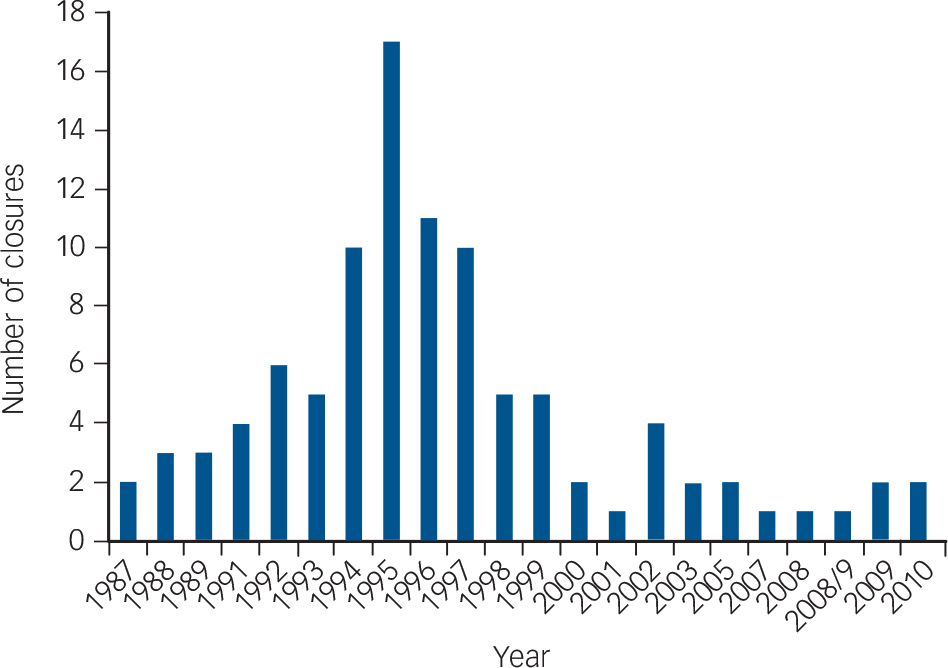

Bed numbers in large psychiatric hospitals peaked in the early 1950s. In 1962 the Hospital Plan for England and Wales predicted the closure of half of these beds by 1975. The decision to close the hospitals and move to a range of community-based services was set out in 1975 in the Better Services for the Mentally Ill white paper. 1 The estimated timescale of 25 years was remarkably prescient, most of the 100 or so had closed by 2000 (the peak year of 1995 saw 17 close) with the remainder shut by 2010 (Fig.1). 2 The closure of the hospitals, and the development of community services had multi-party political support. In retrospect, the scale and pace of change was remarkable.

Fig. 1 The frequency of closure of the large psychiatric hospitals in England by year.

Source: The Asylums List (2014). 2

The rise of private sector placements

One legacy of the psychiatric hospital closure programme has been the use of private sector facilities for those needing longer-term care and support, or who are deemed to be challenging to local services, i.e. treatment resistant, have highly complex needs and are reluctant to engage. These placements are know as ‘out of area treatments’ (OATs). It has been argued that the use of OATs has created virtual asylums. Reference Killaspy3,Reference Poole, Ryan and Pearsall4 Smaller scale but often locked establishments with little or no focus on quality assurance and decreasing scrutiny from regulators. A depressing resonance with the private mad houses of the 19th century.

Subsequent mental health policy has focused more on the care processes, and teams needed (for example, as described in the National Service Framework for Mental Health (NSF) and subsequent Policy Implementation Guides), with specific attention on early detection, rapid treatment and reduced admission. But there is one group of users who have been largely ignored. They have longer-term needs, mostly with psychosis and they need extended periods of admission with considerable ongoing support and care as a result of the complexity of their problems. In short, they need rehabilitation – something that was largely absent from the NSF, which set out a plan for the development of services over a period of 10 years from 1999 to 2009. As Holloway Reference Holloway5 noted in this context: some effective rehabilitation teams were rebadged as assertive outreach teams; health and social care placements were spot purchased by commissioners creating a virtual asylum largely in the private sector; long-stay in-patient beds did not fit well with a managerial ethos focused on decreased lengths of time in in-patient beds; failure to respond to treatment for psychosis was downplayed by evidence-based practice; psychiatric rehabilitation became seen as a redundant concept in the midst of hospital closure. In short, Holloway concluded that psychiatric rehabilitation became unfashionable in a world supposedly driven by functional, evidence-based, mental health teams and the harsh realities of budgetary restriction.

Despite the loss of coherent rehabilitation services during the implementation of the NSF, Killaspy et al (2005) Reference Killaspy, Harden, Holloway and King6 in a national survey identified 2200 National Health Service (NHS) rehabilitation beds. Many of these services also employed community rehabilitation teams. In addition, however, Hatfield and colleagues Reference Hatfield, Ryan, Simpson and Sharma7 showed just how variable the ongoing use of private sector rehabilitation placements was for those with a diagnosis of psychosis. This study took place in seven strategic health authority areas covering some 24% of the total English population. In total, 3500 adults were placed, 40% of whom had a psychosis. The proportion of placements located over 20 miles or more from the adult's neighbourhood varied from 16 to 54%.

The financial cost of OATs

How much do OATs cost? Ryan et al Reference Ryan, Pearsall, Hatfield and Poole8 calculated the average cost of an OAT, for 70 people with a severe and enduring mental illness, from one primary care trust and one social services department. The majority of this group were placed in the private sector with an annual cost of £30 800 per annum. In addition, 64% were not on the care programme approach; most were in locked facilities although informal patients (79%); 50% had no clinical history taken and nearly one-third required supported accommodation rather than independent care.

In an article by David Brindle Reference Brindle9 Killaspy's work with the Royal College of Psychiatry's Policy Unit was cited. They sent a Freedom of Information request to all English primary care trusts and local authorities to try to get a clearer national picture of the number and cost of OATs. The survey found a total of 6280 OATs, costing some £220 m. The average cost was £35 000 a year, compared with £22 000 for an equivalent placement in a local rehabilitation service. Thus, an NHS placement is 32% less expensive than the private sector equivalent. Extrapolated to take account of non-respondents, overall spending on OATs was calculated at £330 m, and their net extra cost was put at £134 m. Although not all OATs are deemed replaceable, Killaspy thinks that almost all those (half the total) made by local authorities are likely to be so, as well as ‘a significant proportion’ of those more complex cases handled by primary care trusts. On this basis, much of the £134 m extra cost could be saved.

A better way forward?

Killaspy and colleagues (2009) had already demonstrated the feasibility of the argument in a formal study based in London. Her team assessed service users in OATs for suitability for relocation to local rehabilitation and supported accommodation. Reference Killaspy, Rambarran, Harden, Fearon, Caren and McClinton10 The study compared the characteristics of individuals placed in OATs with those of local rehabilitation service users in order to identify gaps in local provision. Over the first 30 months, 51 individuals placed in OATs were identified and 40 reviewed. Standardised assessment data were compared with local rehabilitation service users' data. The findings from the study showed that individuals placed in OATs had a greater range of diagnoses and more had alcohol dependency than local service users. Ratings of social function were similar. Of 25 individuals (63%) in OATs assessed as suitable to move, 13 (33%) relocated, all to more independent accommodation. Associated financial flows were reinvested into new local highly supported flats. The study concluded that a significant proportion of individuals placed in OATs could be successfully relocated to more independent local facilities.

In recent years, more attention has been paid to the needs of this client group. Rehabilitation services can now become accredited through the AIMS system, an initiative of the Royal College of Psychiatrists' Centre for Quality Improvement. In 2011, The Royal College of Psychiatrists published a toolkit on good practice in relation to OATs, which was commissioned by the Department of Health as part of their QIPP (Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention) initiative. Reference Ryan, Davies, Bennett, Meier and Killaspy11 The Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health also emphasised the need for local and integrated responses. 12 In recent years there have been encouraging signs of a revitalised approach to commissioning in this area. For example, in Tees, Esk and Wear Valley NHS Foundation Trust, the West Park Unit for people with long-term needs and challenging behaviour practice intensive rehabilitation focused on recovery. The Unit is AIMS accredited. In another example, a consortium of commissioners in Lancashire are launching an initiative in partnership with local providers and social care organisations to develop local alternatives. Key among their ideas is the dedicated case manager for people with long-term needs placed out of area.

Despite these examples of innovation above, the anecdotal evidence is that rehabilitation services are facing serious cuts and reconfigurations of their services. The demonstrable determination of those working in the rehabilitation field is heartening. Reference Killaspy, Marston, Green, Harrison, Leon and Cook13 But is it enough? There is a natural temptation to call for a national policy to set out the ways for providing the best service for this complex population. But policy documents can be a two-edged sword; limiting innovation, as they standardise practice. Perhaps it is better to enable a profession-wide dialogue, backed with the latest expertise and practice, based on the evidence that is now emerging. Can it really be sensible to continue wasting money on spot-contracted OATs, at a time when there is considerable pressure on both mental health and local authority budgets, instead of investing in well-trained staff working in local rehabilitation teams, supported by dedicated case managers all underpinned by re-commissioned ‘cost and volume’ contracts i.e. where commissioners guarantee to buy a minimum level of service at a set price with the option to add additional placements if needed. Whole system commissioning and provision is required, reducing the gap between organisations, creating a free-flowing pathway that hastens improvement for this deserving group.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.