Many randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have reported beneficial effects for omega-3 highly unsaturated fatty acids (HUFAs) in bipolar and major depressive disorder, but others have reported essentially no effect. Reference Andreeva, Galan, Torres, Julia, Hercberg and Kesse-Guyot1–Reference van de Rest, Geleijnse, Kok, van Staveren, Hoefnagels and Beekman35 Since Ross and colleagues, in 2007, Reference Ross, Seguin and Sieswerda36 initially explored the reasons for discrepant findings, subsequent meta-analyses have also identified these possible explanatory factors: (a) that only eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA)-predominant formulations of omega-3 HUFA have an antidepressant effect; Reference Martins, Bentsen and Puri37,Reference Sublette, Ellis, Geant and Mann38 and (b) that the putative antidepressant effects of omega-3 HUFAs only occur in episodes of diagnosed clinical depression. Reference Appleton, Hayward, Gunnell, Peters, Rogers and Kessler39,Reference Appleton, Rogers and Ness40 In contrast, the meta-analysis in 2012 by Bloch & Hannestad Reference Bloch and Hannestad41 and Bloch Reference Bloch42 attributed the evidence for benefit of omega-3 HUFAs in prior meta-analyses to publication and other biases, and concluded that the small to negligible effect on depressive symptoms did not justify further funding for large clinical trials as a result of the heterogeneity of results and publication bias. It is important to note that heterogeneity in meta-analyses can be mistakenly attributed to publication bias, including inappropriate study populations or inclusion of ineffective treatment formulations. Consequently, we examined whether omega-3 HUFAs have efficacy for the treatment of depression with specific attention to evaluating potential sources of heterogeneity, for example differing compositions of EPA in the intervention agents, that could account for the discrepancy in results in an attempt to determine whether there is sufficient evidence to justify further clinical trials, and if so, how such trials would be best conceptualised, designed and performed. There are substantial biological differences between docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and EPA, EPA having a greater anti-inflammatory effect in the brain compared with DHA, which may contribute to its putative greater antidepressant effect. Reference Caughey, Mantzioris, Gibson, Cleland and James43 Furthermore, it has been postulated that unopposed EPA (the modest excess of EPA compared with DHA) is the mechanism for its putative antidepressant effect. Reference Sublette, Ellis, Geant and Mann38 We consider this in detail in the Discussion.

There are several reasons why studies should be differentiated by the severity of participant symptoms. Antidepressants for example have greater therapeutic efficacy for individuals with moderate to severe depression compared with mild depression. Reference Kirsch, Deacon, Huedo-Medina, Scoboria, Moore and Johnson44 This is potentially because of the larger placebo response, ‘floor effects’, or regression to the mean, observed in studies of mild depression. Reference Kirsch, Deacon, Huedo-Medina, Scoboria, Moore and Johnson44,Reference Fournier, DeRubeis, Hollon, Dimidjian, Amsterdam and Shelton45 Studies of primary or secondary prevention have additional methodological requirements, including adequate statistical power (see Discussion). Here we focused solely on studies designed to prevent or treat depressive symptoms in the context of affective disorders (major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder), as other meta-analyses have not demonstrated therapeutic efficacy for depressive symptoms in the context of other disorders such as schizophrenia, autism and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Reference Ross, Seguin and Sieswerda36,Reference Appleton, Rogers and Ness40

Our principal hypothesis in this exploratory hypothesis-testing meta-analysis is that, compared with placebo, EPA-predominant formulations would demonstrate superior efficacy among participants with operationally diagnosed clinical acute depression (for example DSM-III-R/DSM-IV or ICD-10). In contrast, no efficacy would be demonstrated among participants with non-clinical depressive symptoms, regardless of the DHA or EPA formulation. This hypothesis-testing meta-analysis is a substantially different form of analysis from a traditional meta-analysis. The can be illustrated best as a tree diagram; the trunk includes all studies, testing one primary hypothesis for no efficacy v. efficacy with analysis then only continuing in the branches demonstrating efficacy (see Fig. 2 in the Results section). We first evaluated whether EPA-predominant formulations (EPA >50% of omega-3 HUFA formulation) would demonstrate greater efficacy for depressive symptoms compared with DHA-predominant formulations (hypothesis 1). The branch demonstrating efficacy was evaluated in hypothesis 2, which predicted that EPA formulations would be efficacious only among patients with a diagnosed clinical depression. The branch demonstrating efficacy was evaluated in hypothesis 3, which predicted that selectively enriched EPA (>80% EPA) (potentially resulting in ‘unopposed EPA’) would have a greater antidepressant effect compared with mixed EPA–DHA formulations (<80% EPA). Hypothesis 4 predicted that omega-3 HUFA supplementation given as an adjunct to antidepressants would display greater efficacy for patients with clinical depression than when given as monotherapy. Hypothesis 5 predicted that longer treatment trials of omega-3 HUFAs would produce a more significant antidepressant effect, and hypothesis 6 predicted that omega-3 HUFAs would have a more substantial antidepressant effect for participants with major depressive disorder compared with bipolar depression. We then examined whether publication bias would account for some of the reported antidepressant efficacy of omega-3 HUFAs.

The logic of this model is to analyse just on a branch that demonstrated efficacy. If both branches demonstrated efficacy, or if there were not enough studies in a branch to continue this model, a conventional meta-analysis was performed where the remaining hypotheses were tested separately. We also undertook extensive sensitivity analysis with alternate definitions of important indices or attributes to ascertain whether findings would be robust under different definitions or assumptions, including testing hypothesis 2 before hypothesis 1, and testing whether there was a dose–response for omega-3 HUFAs or EPA in hypothesis 1 and 3. This study including predefined hypotheses, and meta-analysis design were previously presented at the 49th American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ACNP) 2010 meeting in Florida, USA. 46

Method

Data sources

We conducted a systematic bibliographic search for studies utilising omega-3 HUFAs in mood disorders from the following databases: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Medline, PsycINFO and EMBASE. We searched for articles published between January 1980 and July 2014 without language restriction, using medical subject heading key words: depression OR depressive disorder OR bipolar affective disorder OR bipolar depression OR bipolar illness OR mood disorder OR affective disorder OR mania OR hypomania AND omega-3 fatty acids, OR omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) OR n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids OR highly unsaturated fatty acid (HUFA) OR eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) OR docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) OR fish oil OR nutritional supplement. We also searched by hand the above references from the papers identified, relevant reviews, Trials Central (http://www.trialscentral.org), Current Controlled Trials (http://controlled-trials.com), Clinical Trials (http://clinicaltrials.gov) and contacted several experts in the field to find any published or unpublished studies.

Study selection

We included double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of adults and children, that examined the antidepressant effect of omega-3 HUFAs either as a monotherapy or when augmented to psychotropic agents in: (a) participants with an operationally diagnosed depressive episode, or in the depressive pole of bipolar disorder or a depressive episode comorbid with an episode of self-harm; and in (b) non-clinical populations at risk for depression in which a subgroup had symptoms of depression.

Data extraction

Four reviewers (I.T.M., S.G., J.M.D. and B.H.) independently assessed and extracted relevant data including participants' clinical characteristics, type and dose of compound administered, trial duration, mean psychometric scores and standard deviations or the risk differences, risk ratios or odd ratios of depressive symptoms. Our primary analysis selected the following hierarchy of psychometric instruments: (a) the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) (n = 17); (b) the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (n = 6); (c) the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (n = 2); (d) the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (n = 5); or (e) other depression scales as appropriate (n = 7) (online Table DS1). Sensitivity analyses were based on the second highest psychometric instrument in the hierarchy.

DHA-predominant trials were defined as those providing higher quantities of DHA (>50%) compared with other omega-3 HUFAs. EPA-predominant trials were categorised as either ‘mixed EPA’ denoting EPA-predominant formulations containing at least 20% DHA; or ‘selectively enriched EPA’, denoting formulations containing at least 80% EPA and less than 20% DHA (online Fig. DS1).

Our primary dichotomous categorisation of severity was to identify studies enrolling participants with a diagnosed depressive/self-harm episode, defined as: (a) being treated for a depressive episode; Reference Freeman, Davis, Sinha, Wisner, Hibbeln and Gelenberg7,Reference Gertsik, Poland, Bresee and Rapaport9,Reference Grenyer, Crowe, Meyer, Owen, Grigonis-Deane and Caputi11,Reference Jazayeri, Tehrani-Doost, Keshavarz, Hosseini, Djazayery and Amini13,Reference Lesperance, Frasure-Smith, St-Andre, Turecki, Lesperance and Wisniewski15,Reference Llorente, Jensen, Voigt, Fraley, Berretta and Heird16,Reference Marangell, Martinez, Zboyan, Kertz, Kim and Puryear19,Reference Mischoulon, Papakostas, Dording, Farabaugh, Sonawalla and Agoston21–Reference Peet and Horrobin25,Reference Rees, Austin and Parker27,Reference Silvers, Woolley, Hamilton, Watts and Watson29,Reference Su, Huang, Chiu and Shen32–Reference Tajalizadekhoob, Sharifi, Fakhrzadeh, Mirarefin, Ghaderpanahi and Badamchizade34,Reference Rogers, Appleton, Kessler, Peters, Gunnell and Hayward47,Reference Lucas, Asselin, Merette, Poulin and Dodin48 (b) in the depressed pole of a bipolar disorder; Reference Bot, Pouwer, Assies, Jansen, Diamant and Snoek2–Reference da Silva, Munhoz, Alvarez, Naliwaiko, Kiss and Andreatini4,Reference Frangou, Lewis and McCrone6,Reference Stoll, Severus, Freeman, Rueter, Zboyan and Diamond31 or (c) with a depressive episode comorbid with self-harm (94% of individuals fulfilled criteria for major depressive disorder and all patients had a BDI >19). Reference Hallahan, Hibbeln, Davis and Garland12 Participants attained a diagnosis of depressive episodes from international diagnostic criteria, such as DSM/ICD, or in one case Reference Bot, Pouwer, Assies, Jansen, Diamant and Snoek2 from a well-validated diagnostic interview (Composite International Diagnostic Interview, CIDI). A second categorisation was used for sensitivity analysis. We also determined depression severity on a four-point scale with ratings undertaken masked by B.H. and J.M.D. with a rank correlation of 0.9 attained (see online Table DS1).

When a study did not separately present data regarding augmentation and monotherapy in individual strata, we classified it with the category used for the majority of the patients in the study. We stratified trial duration at ⩽12 weeks v. >12 weeks and the dose of EPA as ⩽0.8 g v. >0.8 g, and total dose of omega-3 HUFA as ⩽1.5 g v. >1.5 g.

Study quality was measured utilising two measures, the Cochrane risk of bias tool, as modified by Corbett & Woolacott, Reference Corbett and Woolacott49 which examines eight potential sources of bias namely: (a) sequence generation, (b) allocation concealment, (c) masking of participants, (d) masking of personnel, (e) masking of outcome assessor, (f) incomplete outcome data, (g) selective outcome reporting and (h) other sources of bias (presented in the online supplement DS1), and the Jadad scale examining randomisation, double blinding and the description of study withdrawals (online Table DS1).

Statistical analysis

We calculated effect sizes for continuous data by attaining the mean (s.d.) and sample size (n) of the omega-3 HUFA and placebo groups. When standard deviations were not available, we estimated these based on the other statistical parameters reported in the study. When continuous data were not available, we evaluated the dichotomous data, calculated odds ratios, which were converted to the Hedge's G effect-size statistic (G). For studies using multiple arms of the drug and one arm of the placebo (for example several omega-3 HUFA doses compared with placebo) the letter ‘n’ entered for each stratum of dose was reduced by dividing by the number of strata (for example if three dosages were utilised, a third of the total n of the placebo group was allocated to each stratum, rounding down when not a whole number). Reference Frangou, Lewis and McCrone6,Reference Giltay, Geleijnse and Kromhout10,Reference Kiecolt-Glaser, Belury, Andridge, Malarkey, Hwang and Glaser14,Reference Mozaffari-Khosravi, Yassini-Ardakani, Karamati and Shariati-Bafghi22,Reference Peet and Horrobin25,Reference Sinn, Milte, Street, Buckley, Coates and Petkov30,Reference van de Rest, Geleijnse, Kok, van Staveren, Hoefnagels and Beekman35,Reference Lucas, Asselin, Merette, Poulin and Dodin48,Reference Chiu, Huang, Chen and Su50 We used Duval & Tweedie's trim and fill test, using a random-effects model on ‘clinical’ studies utilising EPA-predominant formulations to assess for publication bias.

‘Comprehensive Meta-Analysis’, Version 2, was used to evaluate any treatment effect between the treatment groups to ascertain the random-model treatment effect size (G), 95% confidence intervals and standard errors (s.e.) for each study and were carried out a number of sensitivity analyses to ratify our results. In the most important sensitivity analysis, we calculated the effect size using the next-highest psychometric instrument from the predefined hierarchy described above. We assessed heterogeneity of intervention using the Cochrane Q, I 2 and tau-square statistics.

Results

Literature search

A copy of the PRISMA diagram, outlining the search strategy of the literature is presented in Fig. 1. This literature search yielded a total of 1255 potentially relevant articles. The titles and abstracts were reviewed and clearly irrelevant articles were discarded. Consequently, 107 articles were examined in depth, with 43 RCTs selected as they satisfied inclusion criteria. Eight studies could not be included because of insufficient meaningful rating data. Reference Mattes, McCarthy, Gong, van Eekelen, Dunstan and Foster20,Reference Chiu, Huang, Chen and Su50–Reference Krauss-Etschmann, Shadid, Campoy, Hoster, Demmelmair and Jimenez54 Two strata of a study Reference Giltay, Geleijnse and Kromhout10 utilised α-linoleic acid (α-LNA) as the predominant omega-3 HUFA administered, and these were only included in the omega-3 HUFA compared with placebo analysis. Consequently, there were 35 studies divided into 53 strata investigating the therapeutic effect of omega-3 HUFAs in 6665 participants compared with placebo in 4373 participants. These studies are detailed in Table DS1, with design issues and any potential threats to validity described. Thirteen strata compared DHA-predominant formulations with placebo, Reference Doornbos, van Goor, Dijck-Brouwer, Schaafsma, Korf and Muskiet5,Reference Freund-Levi, Basun, Cederholm, Faxen-Irving, Garlind and Grut8,Reference Grenyer, Crowe, Meyer, Owen, Grigonis-Deane and Caputi11,Reference Llorente, Jensen, Voigt, Fraley, Berretta and Heird16,Reference Makrides, Gibson, McPhee, Yelland, Quinlivan and Ryan18,Reference Marangell, Martinez, Zboyan, Kertz, Kim and Puryear19,Reference Mozaffari-Khosravi, Yassini-Ardakani, Karamati and Shariati-Bafghi22,Reference Poppitt, Howe, Lithander, Silvers, Lin and Croft26,Reference Rees, Austin and Parker27,Reference Silvers, Woolley, Hamilton, Watts and Watson29,Reference Sinn, Milte, Street, Buckley, Coates and Petkov30,Reference Rogers, Appleton, Kessler, Peters, Gunnell and Hayward47 17 strata compared selectively enriched EPA formulations with placebo, Reference Bot, Pouwer, Assies, Jansen, Diamant and Snoek2,Reference Frangou, Lewis and McCrone6,Reference Gertsik, Poland, Bresee and Rapaport9,Reference Jazayeri, Tehrani-Doost, Keshavarz, Hosseini, Djazayery and Amini13–Reference Lesperance, Frasure-Smith, St-Andre, Turecki, Lesperance and Wisniewski15,Reference Mischoulon, Papakostas, Dording, Farabaugh, Sonawalla and Agoston21–Reference Nemets, Stahl and Belmaker23,Reference Peet and Horrobin25,Reference Lucas, Asselin, Merette, Poulin and Dodin48 and 22 strata compared mixed-EPA formulations to placebo. Reference da Silva, Munhoz, Alvarez, Naliwaiko, Kiss and Andreatini4,Reference Hallahan, Hibbeln, Davis and Garland12,Reference Nemets, Nemets, Apter, Bracha and Belmaker24,Reference Rondanelli, Giacosa, Opizzi, Pelucchi, La Vecchia and Montorfano28,Reference Su, Huang, Chiu and Shen32 Eighteen strata evaluated studies for stand-alone major depressive disorder, Reference Gertsik, Poland, Bresee and Rapaport9,Reference Grenyer, Crowe, Meyer, Owen, Grigonis-Deane and Caputi11,Reference Jazayeri, Tehrani-Doost, Keshavarz, Hosseini, Djazayery and Amini13,Reference Lesperance, Frasure-Smith, St-Andre, Turecki, Lesperance and Wisniewski15,Reference Marangell, Martinez, Zboyan, Kertz, Kim and Puryear19,Reference Mischoulon, Papakostas, Dording, Farabaugh, Sonawalla and Agoston21–Reference Peet and Horrobin25,Reference Silvers, Woolley, Hamilton, Watts and Watson29,Reference Su, Huang, Chiu and Shen32,Reference Rogers, Appleton, Kessler, Peters, Gunnell and Hayward47,Reference Lucas, Asselin, Merette, Poulin and Dodin48 3 strata evaluated bipolar disorder, Reference Frangou, Lewis and McCrone6,Reference Stoll, Severus, Freeman, Rueter, Zboyan and Diamond31,Reference Keck, Mintz, McElroy, Freeman, Suppes and Frye55 6 strata examined depressive symptoms in the perinatal/postnatal period, Reference Doornbos, van Goor, Dijck-Brouwer, Schaafsma, Korf and Muskiet5,Reference Freeman, Davis, Sinha, Wisner, Hibbeln and Gelenberg7,Reference Llorente, Jensen, Voigt, Fraley, Berretta and Heird16,Reference Makrides, Gibson, McPhee, Yelland, Quinlivan and Ryan18,Reference Rees, Austin and Parker27,Reference Su, Huang, Chiu, Huang, Huang and Chang33 12 strata examined depressive symptoms in elderly people Reference Freund-Levi, Basun, Cederholm, Faxen-Irving, Garlind and Grut8,Reference Kiecolt-Glaser, Belury, Andridge, Malarkey, Hwang and Glaser14,Reference Rondanelli, Giacosa, Opizzi, Pelucchi, La Vecchia and Montorfano28,Reference Sinn, Milte, Street, Buckley, Coates and Petkov30,Reference Tajalizadekhoob, Sharifi, Fakhrzadeh, Mirarefin, Ghaderpanahi and Badamchizade34,Reference van de Rest, Geleijnse, Kok, van Staveren, Hoefnagels and Beekman35 9 strata examined participants with depression and comorbid cerebrovascular or coronary heart disease, Reference Andreeva, Galan, Torres, Julia, Hercberg and Kesse-Guyot1,Reference Carney, Freedland, Rubin, Rich, Steinmeyer and Harris3,Reference Giltay, Geleijnse and Kromhout10,Reference Poppitt, Howe, Lithander, Silvers, Lin and Croft26 2 strata evaluated depression in Parkinson's Disease, Reference da Silva, Munhoz, Alvarez, Naliwaiko, Kiss and Andreatini4 1 stratum evaluated depression in participants with self-harm (suicide attempts) Reference Hallahan, Hibbeln, Davis and Garland12 and 1 stratum evaluated depression in diabetes mellitus. Reference Bot, Pouwer, Assies, Jansen, Diamant and Snoek2

Fig. 1 Flow chart of literature search and study selection.

EPDS, Edinburgh Post-Natal Depression Scale.

Figure 2 emphasises the most important statistical parameter: the change in effect size in the tree branches. Our focus was on whether the hypothesis is confirmed by a clinically meaningful effect size (G) v. an essentially zero effect size. The shaded areas indicate visually the effect size, which is stated within the box. As a result of the ordered nature of the hypotheses, there are fewer studies in every subsequent branch, and effect sizes may increase or decrease. Past the third branching, there were too few studies to justify further branching. Therefore, we conducted conventional meta-analyses for the remaining hypotheses. The distribution of omega-3 HUFA used in these studies was trimodal, (online Fig. DS1). All but two studies Reference Gertsik, Poland, Bresee and Rapaport9,Reference Rogers, Appleton, Kessler, Peters, Gunnell and Hayward47 fell within the following 3 groups; 0–30% EPA (mean 15%), 55–75% EPA (mean 61%) and 85–100% EPA (mean 96%).

Fig. 2 Tree diagram.

When a group's effect size (G) or number of strata (s) approaches zero no further analysis occurs. The width of the blue line is proportional to the number of trials in the following group. The area of the box under a group is proportional to its effect size. The grey boxes contain groups hypothesised to decrease effect size and the blue boxes contain groups hypothesised to increase effect size. Two strata had neither docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) nor eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, n = 1365).

Hypothesis 1: EPA- v. DHA-predominant samples

EPA-predominant formulations demonstrated a superior antidepressant efficacy compared with placebo (G = 0.34, 95% CI 0.21–0.47, P<0.001, I 2 = 61%). In contrast, DHA-predominant preparations consistently demonstrated no benefit over placebo (G = 0.03, 95% CI −0.12 to 0.19, P<0.66, I 2 = 35%). All the fixed and mixed output of both the primary analyses are presented in the online supplement.

Hypothesis 2: diagnosed depression v. undiagnosed samples

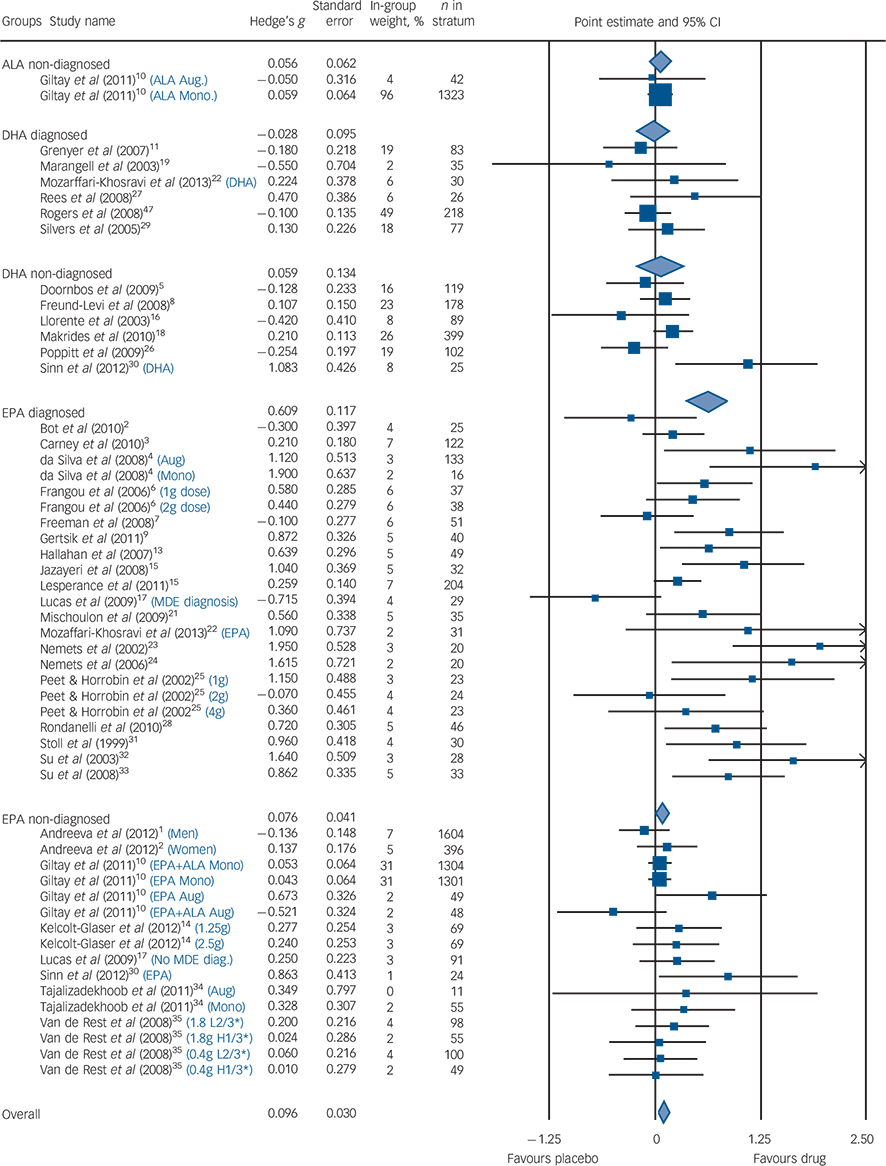

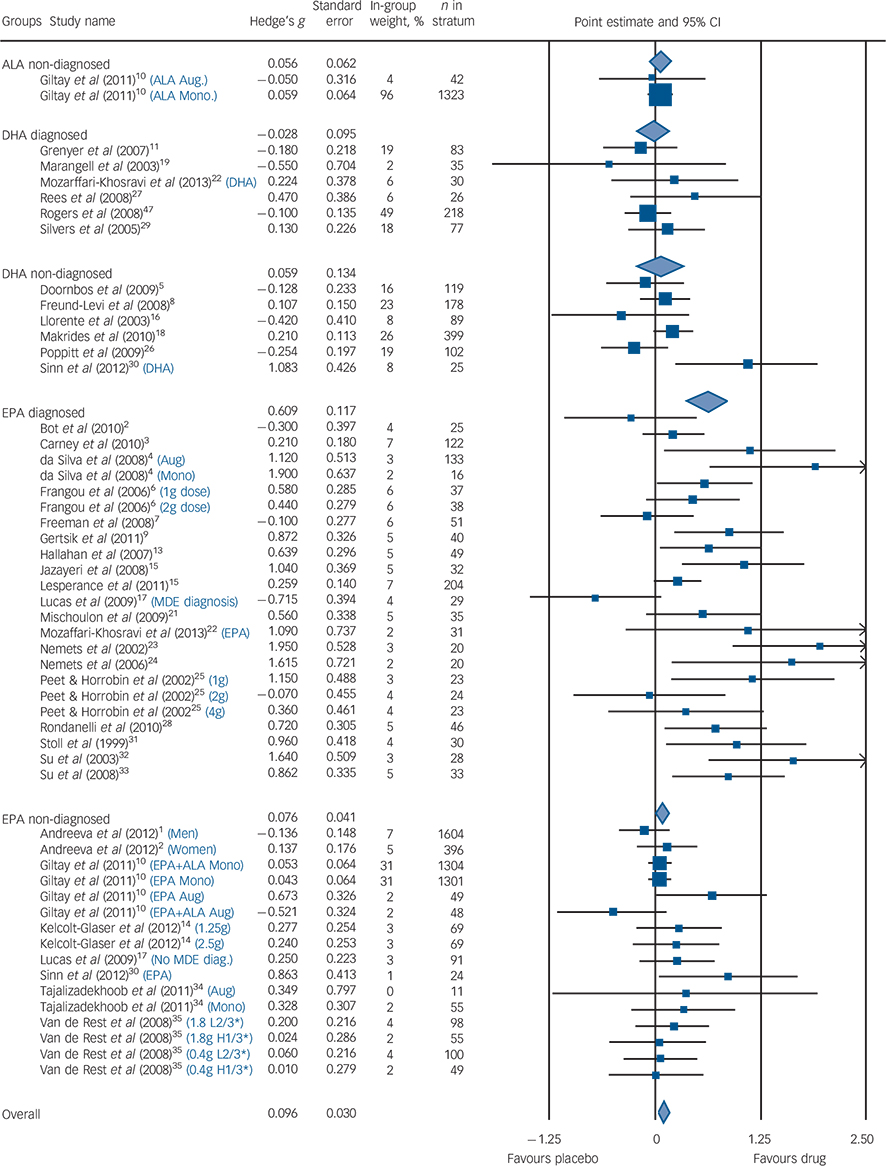

Among populations with a diagnosed depressive episode, EPA-predominant formulations demonstrated a significant benefit compared with placebo (G = 0.61, 95% CI 0.38–0.85, P<0.001, I 2 = 61%), with no benefit consistently demonstrated for the populations without a formal diagnosis of depression (G = 0.08, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.17, P<0.07, I 2 = 5%). The diagnosed depression group was more heterogeneous than the non-diagnosed group. These findings were corroborated by both sensitivity analyses. Our meta-regression found that higher rating of severity was associated with high efficacy compared with placebo (z = 4.7, P<0.001). The forest diagram (Fig. 3) shows virtually the same results. Effect sizes for studies utilising DHA-predominant formulations in both diagnosed depression and undiagnosed depression are also presented in Fig. 3, with no evidence for benefit over placebo demonstrated for either analysis.

Fig. 3 Forest plot.

Size of blue squares proportional to weight in meta-analysis. Size of diamonds proportional to standard error of group. Black lines, show confidence intervals. The blue text indicates that a study was split into multiple strata and the criteria used to do so. H1/3* is the strata with the highest tertile of baseline depression scores; L2/3* is the strata with the lowest two teriles of baseline depression scores. ALA, α-linolenic acid; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; MDE, major depressive episode; Aug, augmentation; Mono, monotherapy.

Hypothesis 3: composition of EPA, selectively enriched EPA v. mixed EPA

Both mixed EPA and selectively enriched (>80%) EPA formulations demonstrated an antidepressant effect. Mixed EPA formulations demonstrated an effect size of 0.62 (95% CI 0.31–0.94, P<0.001, I 2 = 68%) and selectively enriched EPA formulations demonstrated an effect size of 0.61 (95% CI 0.26–0.96, P = 0.001, I 2 = 49%), with the heterogeneity between groups not significant. Sensitivity analyses corroborated these findings.

Hypothesis 4: augmentation and monotherapy

Compared with placebo, EPA was effective in both augmentation (G = 0.59, 95% CI 0.42–0.77, P = 0.004, I 2 = 57%) and monotherapy (G = 0.33, 95% CI 0.13–0.52, P<0.003, I 2 = 68%). This again was corroborated by sensitivity analysis. Augmentation studies demonstrated a trend towards greater antidepressant efficacy compared with monotherapy studies (P = 0.07) (which is consistent with the one direct study demonstrating greater efficacy in augmentation studies Reference Jazayeri, Tehrani-Doost, Keshavarz, Hosseini, Djazayery and Amini13 ).

Hypothesis 5: duration

The median duration for all trials was 12 weeks, which is also concordant with animal studies for brain omega-3 HUFA restoration. We failed to find any evidence of greater clinical efficacy among longer trial durations (i.e. >12 weeks). Trials of both <6 weeks (G = 0.55, 95% CI 0.30–0.81, P<0.001, I 2 = 57%) and >6 weeks (G = 1.07, 95% CI 0.21–1.93, P = 0.02, I 2 = 79%) demonstrated clinical efficacy. However, all trials assessing clinical depression with omega-3 HUFAs were relatively short in duration (⩽26 weeks, median 11 weeks). There was no evidence of a linear relationship when individual trial length was plotted against effect size (see online supplement DS1).

Hypothesis 6: EPA in bipolar depression

The effect size for bipolar depression was 0.59 (95% CI 0.24–0.94, P<0.001, I 2 = 0%), however there were too few strata (n = 3) to make any definitive conclusions.

Publication bias

The Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill test, using a random-effects model on diagnosed depression studies where EPA was the predominant formulation, estimated that several studies with negative effect sizes might never have been published (Fig. 4). The adjusted values with the imputed studies reduced the effect size from G = 0.61 to G = 0.42 (95% CI 0.18–0.65, P<0.001).

Fig. 4 (a) Effect size in diagnosed and non-diagnosed studies; (b) funnel plot of standard error by effect size in eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), diagnosed group.

In (a) each white dot represents one study and its effect size; the blue line represents the median effect size for the group and the grey line goes across the zero point (no difference between drug and placebo). In (b) each white dot represents a real study; each blue dot represents an imputed study; the white diamond indicates the calculated effect size, extending left and right to show 95% confidence intervals; the blue diamond indicates the imputed effect size, extending left and right to show 95% confidence intervals; the blue triangle outlines the ‘funnel’, centred at the imputed effect size and the blue vertical line extends upward, centred at the imputed effect size.

Discussion

Main findings

Our purpose was to understand why some controlled studies found omega-3 HUFAs efficacious and other did not. Bloch Reference Bloch42 and Bloch & Hannestad Reference Bloch and Hannestad41 attributed heterogeneous results to publication bias, concluding that no further clinical trials should be undertaken and that state agencies should spend their research dollars elsewhere. Since evaluating the correct formulation in an inappropriate population or evaluating an inactive preparation in a sensitive population can confound results, we explored omega-3 HUFA formulations and grades of depression simultaneously, to explain the reasons for these discrepant results. This systematic review and exploratory hypothesis-testing meta-analysis, testing multiple, predefined ordered hypotheses demonstrated that EPA-predominant formulations are more efficacious than placebo for treatment of clinical depression. DHA-predominant formulations are consistently and homogenously ineffective. All formulae are also consistently and homogenously ineffective in non-depressed populations. We can confirm the findings of Bloch & Hannestad that publication bias exists, but disagree with their conclusion that a definitive confirmation study should not be undertaken; their verdict of ‘not yet proven’ is not definitive proof of absence of efficacy. Indeed, we insist that a positive finding with publication bias specifically suggests that multicentre RCTs of EPA-predominant formulations, with attention to the diagnostic confirmation and severity of depression, can now be appropriately powered and conducted.

Publication and other biases

The effect size for EPA-predominant formulations in clinical depression (G = 0.61) is comparable with that of conventional antidepressants but high or statistically significant effect sizes do not in themselves demonstrate a genuine effect. There is a widespread phenomenon for earlier small studies to have larger effect sizes than later larger studies. We can confirm Bloch & Hannestad's Reference Bloch and Hannestad41 finding of publication bias as we found, using Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill test, using both random- (G = 0.42) and fixed-effect models (G = 0.47), a reduction in the effect size in relation to the antidepressant efficacy of EPA. We found evidence of potential publication bias with the magnitude of effect increased in strata of under 40 participants (see online supplement DS1). Whereas the overall mean stratum size was 207 participants, the mean stratum size for studies in diagnosed depression using EPA formulae was 42 with 74% of strata having less than 42 participants. We largely replicated, except in one instance, the Jadad ratings of study quality of Bloch & Hannestad Reference Bloch and Hannestad41 (see online supplement DS1 for this and the Cochrane risk of bias tool).

Biological plausibility

The putative role of omega-3 HUFAs in the treatment of depression is biologically plausible, a hypothesis supported by epidemiological observations, tissue compositional comparisons, clinical and treatment studies in a large, complex and not entirely consistent literature. Reference Appleton, Rogers and Ness40 Humans are unable to synthesise EPA or DHA de novo and make limited amounts of DHA and EPA from the dietary precursor alpha-linolenic acid (ALA). Fish and shellfish are the primary dietary sources of pre-formed EPA and DHA, and epidemiological or tissue studies cannot disentangle the respective role of EPA from DHA.

Our analysis of differences comparing EPA or DHA v. placebo is indirect. There is only one study with direct comparison between EPA and DHA in patients with depression, demonstrating clear superiority for the EPA-predominant formulation over DHA or placebo. Reference Mozaffari-Khosravi, Yassini-Ardakani, Karamati and Shariati-Bafghi22 Mixed-EPA formulations where DHA was present in significant quantities proved to be clinically effective to at least the same degree as ‘selectively enriched’ EPA formulations. The RCT studies that have been published since Sublette et al's Reference Sublette, Ellis, Geant and Mann38 theory of antidepressant efficacy relating to EPA being unopposed by DHA, support such a hypothesis, although there have been no recent studies assessing the antidepressant effects of ‘super-high’ doses of EPA.

Several different mechanisms of antidepressant effects for both EPA and DHA can be postulated. DHA is highly enriched in brain synaptosomal membrane phospholipids, where it alters the biophysical properties of membranes, enhances neurotransmission, Reference Nemets, Stahl and Belmaker23 increases inflammation resolution Reference Kim56 and neurogenesis, Reference McNamara, Able, Liu, Jandacek, Rider and Tso57 all of which have plausible beneficial effects for mood disorders. These central actions are, however, dependent on the enrichment of DHA in brain tissue from circulating unesterified DHA. Low levels of DHA have been reported in post-mortem orbitofrontal cortex of patients with major depression. Reference Moriguchi, Loewke, Garrison, Catalan and Salem58 The complete restoration of DHA into the brain is about 12 weeks from deficiency states in animals. Reference McNamara, Hahn, Jandacek, Rider, Tso and Stanford59 However, in the replete steady state, DHA turnover in human brain is slow, with a half-life of approximately 2.5 years. Reference Umhau, Zhou, Carson, Rapoport, Polozova and Demar60 Omega-3 HUFAs to date have not been evaluated in participants with significant clinical depression beyond 16 weeks; our findings suggest that an emerging antidepressant effect may be evident at 4 weeks post-treatment.

A putative novel mechanism differentiating EPA from DHA

The late David Horrobin initially hypothesised that EPA had a superior beneficial antidepressant effect to DHA, suggesting that EPA probably works by modulating post-receptor signal transduction processes. Reference Horrobin61 Here we posit a novel mechanism for EPA potentially underlying the selective reduction of significant depressive symptoms as compared with DHA. Although EPA is not abundant in the brain at steady state, EPA rapidly enters the brain as a free fatty acid and is not reacylated into phospholipid membrane stores, being rapidly metabolised and beta oxidised. Reference Chen, Domenichiello, Trepanier, Liu, Masoodi and Bazinet62 EPA is the natural ligand for the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) nuclear transcription receptor that downregulates expression of nuclear factor-kappa B (Nf-κB) and inhibits neuronal parainflammatory cascades implicated in the pathophysiology of dysregulated stress responses and depression. Reference Gold, Licinio and Pavlatou63 Free fatty acids activate PPARs by stabilising the activation function 2 (AF-2) helix; carbon atom (C) lengths shorter than C16 fail to stabilise and greater than C20 (such as DHA 22:6n-3) fail to fit in the ligand binding pocket, with PPARγ having the greatest fatty acid specificity. Reference Xu, Lambert, Montana, Parks, Blanchard and Brown64 Low concentrations EPA (20:5n-3) bind with very high affinity to all PPARs Reference Lin, Ruuska, Shaw, Dong and Noy65 and 20:5n-3 co-crystals have been characterised, Reference Xu, Lambert, Montana, Parks, Blanchard and Brown64 but in contrast, the binding affinity of DHA to PPARγ is so low it cannot be measured. Reference Lin, Ruuska, Shaw, Dong and Noy65 Although several studies have reported that adding DHA to diets or model systems activates PPARγ, this may be attributable to retro conversion of DHA to EPA. Reference Jump, Tripathy and Depner66 In addition the DNA binding-independent transactivity, that indicates the formation of the PPARα-associated coactivator-transcriptional complex PPARα–retinoid X receptor alpha (RXRα), is promoted by polyunsaturated fatty acids of 18 to 20 carbon groups with 3–5 double bonds, but not by DPA n-3 or DHA. Reference Mochizuki, Suruga, Fukami, Kiso, Takase and Goda67 EPA increases transactivation of PPARα–RXRα at low concentrations (1–10 μM) whereas in contrast DHA inhibited transactivation of PPARα–RXRα at concentrations higher than 50 μM. Reference Popeijus, van Otterdijk, van der Krieken, Konings, Serbonij and Plat68 Since DHA is at high concentrations in the brain at steady state it may provide tonic inhibition of PPARs, whereas transient low concentrations of EPA may activate PPARγ. The selective discrimination of EPA from DHA in activating PPARγ–RXR nuclear transcription regulating the Nf-κB parainflammatory pathway is consistent with a proof-of-concept trial of the PPARγ agonist pioglitazone for depressive symptoms Reference Kemp, Schinagle, Gao, Conroy, Ganocy and Ismail-Beigi69 and may extend to other psychiatric illnesses including preventing alcohol relapse. Reference Stopponi, Somaini, Cippitelli, Cannella, Braconi and Kallupi70

In contrast to DHA, supplemental EPA is rapidly incorporated into membrane phospholipids of circulating mononuclear cells, resulting in attenuated production of proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα). Reference Caughey, Mantzioris, Gibson, Cleland and James43 Increased circulating IL-1 and TNFα occur in people with major depressive disorder; perhaps the therapeutic antidepressant effects of EPA may be related in some part to its anti-inflammatory effect. Indeed, EPA downregulates the release of inflammatory cytokines that can produce clinical symptoms of depression, especially IL-1β, TNFα and IL-6. Reference Maes, Yirmyia, Noraberg, Brene, Hibbeln and Perini71 Inflammatory biomarkers are associated with an antidepressant response to EPA monotherapy whereas DHA is not. Reference Rapaport, Nierenberg, Schettler, Kinkead, Cardoos and Walker72 Individuals with elevated interferon (IFN)-α as a result of chronic hepatitis C frequently experience fatigue, arthralgia and myalgia and many fulfil operational diagnostic criteria for depression. These patients respond to antidepressants. Reference Sarkar and Schaefer73 Similarly, in a recent, RCT, EPA but not DHA was also noted to ameliorate IFN-α-induced depression. Reference Su, Lai, Yang, Su, Peng and Chang74

In the rodent olfactory bulbectomy depression model, EPA treatment normalised depressive behaviours by attenuating prostaglandin E2-mediated activation of IL-6, decreasing mRNA expression for corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) and inhibiting hyperactivation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. Reference Song, Zhang and Manku75 EPA may also exert a greater neurotrophic effect compared with DHA, with EPA supplementation shown to increase brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels after traumatic brain injury. Reference Wu, Ying and Gomez-Pinilla76,Reference Rao, Hattiangady and Shetty77 BDNF has been linked with the ‘neurotrophic hypothesis’ such as: (a) impairment of hippocampal BDNF signalling produces certain depression-related behaviours and impairs the actions of antidepressants; Reference Taliaz, Stall, Dar and Zangen78 (b) experimental increases in hippocampal BDNF levels produce antidepressant-like effects; Reference Hoshaw, Malberg and Lucki79 and (c) EPA's antidepressant effect may be in some part related to its ability to enhance dopaminergic and serotonergic neurotransmission. Reference McNamara, Able, Liu, Jandacek, Rider and Tso57

Clinically diagnosed depression v. symptoms in non-clinical populations

Our primary distinction to separate episodes of diagnosed depressive illness from milder depressive symptoms among non-clinical populations at risk for depression was a dichotomous classification. It was supported by both a sensitivity analysis using alternative criteria and a meta-regression analysis based on the grade of depression present, from diagnosed clinical depression in individuals seeking treatment to mild symptoms of depression in a non-clinical population. Of note, one recent meta-analysis Reference Grosso, Pajak, Marventano, Castellano, Galvano and Bucolo80 also demonstrated a benefit for depressive symptoms in non-clinical depression, however their inclusion criteria for this group were significantly different to ours, potentially explaining this difference in results. In augmentation studies, patients must be sufficiently depressed to require antidepressants, and may have treatment-resistant depression. In contrast, monotherapy studies sometimes explicitly exclude patients with moderate to severe depression and in any case such patients may not be referred if antidepressants were clearly needed. Other methodological problems include large placebo effects, regression to the mean and frequency of prior episodes in studies of prophylactic antidepressants to prevent relapse. Changes in mood in non-clinical populations may not be the same thing as in clinical depression. This dimension is important in clinical trial design and we discuss it in more detail in the online supplement. In contrast to a recent meta-analysis, Reference Grosso, Pajak, Marventano, Castellano, Galvano and Bucolo80 EPA-predominant formulations demonstrated antidepressant efficacy both as augmentation agents and in monotherapy. Meta-analyses Reference Appleton, Sallis, Perry, Ness and Churchill81 that do not appropriately evaluate the dimensions of both clinical severity and use of EPA-predominant formulations may underestimate clinical effect sizes and prematurely conclude that n-3 HUFA interventions have only limited therapeutic utility.

Other limitations

General limitations of meta-analyses include issues such as limitations of available studies of varying quality, non-uniformity of formulations, duration of trials and that this meta-analysis itself is not a randomised selection of trials, but rather an observational analysis of existing trials. Many of the studies did not have the assessor guess the participants' consumption (active omega-3 HUFA formulation or placebo). Treatment adherence and/or the alteration in lipid compositions secondary to omega-3 HUFA intake were similarly not measured in most studies. We did not explore issues relating to tolerability of omega-3 HUFAs in this study.

Implications

Omega-3 HUFAs with EPA-predominant formulations demonstrated evidence for an antidepressant effect both when used alone and as augmentation agents for operationally diagnosed episodes of depression in contrast to DHA-predominant compounds where no antidepressant efficacy was demonstrated. This suggests that larger multisite, RCTs testing the clinical antidepressant efficacy and safety of EPA-predominant formulations both in monotherapy and as an augmentation agent in populations with clinical depression are warranted. We recommend that such studies should be accompanied by monitoring of treatment adherence including monitoring of biochemical levels of omega-3 HUFAs. Furthermore, studies should aim to determine optimal dose, enrol patients with major depression who have moderate to severe symptoms, with the methodological protocols used in clinical trials and ascertain how their putative therapeutic actions add to, and interact with, conventional antidepressant agents.

Funding

The intramural programme of the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism provided support for this work.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge J.P.S. as originating the idea that selective binding at PPARγ may explain the differential efficacy of EPA, and Rachel Gow for her work in proofreading this article.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.